All of the kids watched TV in the basement. Wyatt sat next to his cousin, Erika, who was playing Fruit Ninja on her tablet. Every once in a while, she passed it to him and he took a turn while she watched.

They had only met once before, when Wyatt was two and Erika was three. Neither remembered the meeting.

Wyatt blinked several times, his eyes dry from the game’s choppy lights and technicolor pulp. A watermelon split down the middle.

He wasn’t sure how long they’d been sitting like this. He also didn’t mind because his mom and dad only let him use the tablet on the weekends and never for more than thirty minutes. Sometimes, if they were on a long drive, they might let him use it a bit longer, but that didn’t happen often. Also, Erika had way more games on it than him.

Wyatt reached for his cup of Sprite on the coffee table, but he couldn’t find it. He excused himself and went upstairs. The adults milled around, chatting in low voices. Occasionally, a man on the TV roared touchdown! or fumble! He moved between the press of bodies until he reached the kitchen, where a display of food and drink lay close.

Withering bags of chips, gaping like dumbstruck mouths. Seven-layer dip that was browning at the bottom. A softening pile of cake truffles.

Wyatt walked past the food and to the big cooler by the doors to the backyard. Inside was a slurry of ice and soda cans. He grabbed a Mello Yello and wrapped it in his shirt because it was too cold against his bare palm. Looking back up, he saw his dad standing on the porch, talking to two men he didn’t recognize. In one hand his dad held a can of beer; in the other, a glowing cigarette. The floodlights made his dad look older than the other two men, lighting up the gray in his beard and the lines around his eyes.

Wyatt went back downstairs.

Erika had given up on Fruit Ninja. Now, she was watching a video. It was a guy with a beard and swoopy hair talking about a video game that Wyatt had never heard of before.

“Have you seen him?” Erika said when he sat down next to her.

Wyatt shook his head. His parents didn’t let him watch YouTube, but he saw some videos at school or at his friends’ houses. He’d never seen this guy, though.

“He’s funny,” she said, refocusing her gaze on the screen.

Wyatt popped the tab on the can and drank.

#

“What does it look like?”

The tracks are soft, but he guesses they’re somewhat old. A sprig stands in the center of one, and muddy water swelling in the other.

“A doe?” Wyatt says.

Next to him, his dad clicks his teeth.

“Maybe. Or it could be a yearling buck, they can look similar.”

Wyatt nods, then frowns and straightens up. His dad gently prods him on the shoulder.

“Don’t worry, it tricks me up all the time,” his dad says, eyes narrowed and scanning the forest.

Somewhere, a woodpecker rings between the trees. Somewhere else, twigs snap, water flows, and birds sing, but everything is muddled beneath each other. This deep into the woods, the sounds, no matter how soft, are overwhelming, like a gauzy blanket smothering your face.

“C’mon,” his dad says. “Let’s see where it takes us.”

#

Erika’s house couldn’t be more different than Wyatt’s. It was about two hours away. It seemed huge when they drove up to it and even bigger when they stepped inside. Wyatt specifically felt like he was stepping into an open mouth as they walked in. The house was in a neighborhood with nothing else around except other houses, which all looked different and also exactly the same.

One thing that surprised him was how many rooms they had. There was a bathroom on the first floor, two upstairs, and a small one in the basement, but only Erika and her parents lived there. They also had an extra bedroom, and the kitchen was so big that there was a table in it, even though they already had a dining room by the foyer. They used that to put extra stuff, like boxes, old furniture and unfolded laundry.

As they pulled up in the car, Wyatt’s mom quietly told his dad that the house was ugly. Wyatt thought it was cool, though. He imagined that he could get lost in it.

#

It must be another hour before Wyatt notices anything again. They’ve proceeded in silence most of the way, his dad stalking ahead and him following. It’s now midday, and while still wet and cold and the sun distant behind pale clouds, Wyatt sweats beneath his clothes. Occasionally, wind moves through, the sweat dries slightly, and he shivers. Then he sweats more, and his skin feels humid, and on it goes.

Judging by his dad’s careful gait, Wyatt knows they’re following something and not simply wandering. He can’t be sure if it’s still the doe that made those tracks. Tracking, though interesting, doesn’t come naturally to him. His dad claims it’s something that you learn, that you could be born with the skills, but if you don’t know the actual techniques, then it’s pointless. He says his dad taught him before he was even Wyatt’s age, and that’s the only reason he’s so good at it now.

As they approach a small clearing, Wyatt stops and points to a low shrub. The stalks are green and shrouded by multiple shoots, some of which have been broken off. Their doe might have been eating from it.

“Maybe it was here?” He says.

His dad’s mouth quirks up, and he nods.

“Yeah, looks like it. Good job.”

Wyatt smiles, too. They spend time in the clearing, estimating how recently the doe must have come through. But even as his dad finds more, Wyatt is in a giddy fog from his discovery.

#

Wyatt got bored and excused himself upstairs again. He wandered through the mess of adults until he found his mom. She sat in the living room with a baby in her lap. The baby wore a bib and sucked on its hand. Its arm looked like a pale sausage.

Wyatt sat next to his mom and laid his head on her shoulder. The cushion beneath him sank more than he’d expected.

“Hi, sweetie,” she said, leaning her head so it rested atop his.

Then she straightened back up and bounced the baby on her lap.

“This is Kennedy,” she said, waving the baby’s non-slobbery hand.

Wyatt waved back. His mom loved babies. She’d talked about giving him a little brother or sister, but it still had yet to happen.

“Wow, he is all you.”

They both looked up to find a woman with a wide, flat face staring down at them. She had crinkled dark hair with purple ends.

“Thank you!” His mom said.

“The hair, the eyes, everything,” the woman said, then looked directly at Wyatt. “How old are you?”

“Eleven.”

“About to be twelve,” his mom said.

The woman didn’t acknowledge her.

“Wow… so big!” She spoke slowly with large eyes as if in a daze. “When’s your birthday?”

“March eighth,” he said.

The woman’s smile grew.

“So soon!” She looked at his mom. “It’s so nice to see you again… it’s crazy. You look just like when I last saw you.”

His mom smiled without showing her teeth. She bounced Kennedy on her lap. The baby looked around with the same dazed look as the woman.

“Well, we’re happy you’re here,” the woman said.

A roar lifted through the room. People raised their cups and bottles. A few people groaned, but they were in the minority. The woman shuffled away.

#

A bit later, they find fresh scat. Wyatt knows it’s fresh because there’s a shine to it and points it out, even though it might be obvious. Still, he wants his dad to know that he knows. His dad pats him on the back and tells him he has a good eye. Wyatt then asks if it’s a buck or a doe. His dad says it’s impossible to tell. Bucks generally produce more than does, but it’s not definite.

As they walk, the sun beats down Wyatt’s neck. He drinks desperately from the bottle, and the drops trickle down his throat, making him cold. Then he and his dad decide to rest, Wyatt chewing on a granola bar while his dad decides where they’ll go next.

#

Wyatt moved around the house again. He thought about how his mom had said that the house was ugly. He didn’t think it was ugly. It was so spacious it almost felt bigger on the inside. There were so many doors, and he knew they led to things like bathrooms and closets, but it was so easy to imagine they could lead to somewhere else entirely.

Now, he wanted to see his dad again. When they’d first arrived, his dad had faded into the crowd while Wyatt’s mom and aunt exchanged hugs. Even though his dad had repeatedly said that the party would be fun and Wyatt should be excited, he sensed his dad didn’t want to be there.

He found him outside, in his big jacket and leaning against the porch railing. He talked to two other men around his age, men with pale buzzcuts and paunchy stomachs. As he approached, he realized they were talking about hunting. There was a surplus of does in the area, so they’d all been doing a harvest.

Because his jacket was in the foyer across the house, Wyatt had neglected to get it. The cold sunk through his clothes and skin, making him feel smaller. He walked up to his dad and pressed himself against him.

“Hey,” his dad said, looking down and wrapping an arm around him. “What’s up?”

Wyatt shrugged and pressed himself further into his dad, into the warm wall of his chest, which smelled of tobacco and laundry detergent.

“You cold?” His dad said.

He nodded. His dad shrugged off his jacket, and Wyatt put it on. The jacket belonged to Wyatt’s grandpa, who was in the Navy. It was bulky and made of a tough, greenish fabric, and the inside was lined with wool. It wasn’t comfortable, but whenever his dad lent it to him, it kept Wyatt warmer than anything else he’d worn.

“This your boy?” One of the men said.

His dad nodded.

“Yep.”

“He’s tall,” the other man said. “Taking after you.”

“I know,” his dad said. “He looks just like his mom, though.”

“Oh, you mean Anne’s sister?” The first man said.

Wyatt’s dad nodded again.

The other men looked at each other. His dad stared at them, and he hadn’t been smiling before, but now his lack of a smile was more pronounced, set harder into his grizzled face.

“He does look just like her,” the second man said, then cleared his throat.

More cheers and groans rose inside, battering the sliding glass doors.

“So, uh, you fish too?” The second man said.

“Nah,” Wyatt’s dad said, shaking his head. “My old man did, but, I dunno, I never got the hang of it.”

“Hm,” the first man said. “My brother does fly fishing. He’s religious about it.”

“Yeah,” the second man said. “People take it really seriously.”

The cheers and groans died down. Wyatt’s cheeks ached from the biting cold. All of the men looked around but not at each other. Then they started talking about hunting again, and Wyatt stayed outside for a few minutes longer.

#

They creep behind a tangle of bushes and look out onto another field. It expands wide, mostly flat before another patch of forest cuts up against the horizon. They hope to see the deer they’re tracking, but the field is empty. Wyatt gets hungry again, and his dad gives him a protein bar. He eats as quietly as he can and barely tastes it, too focused on the field. Inevitably, his mind wanders to other things, though. What will they have for dinner? Can his mom help him with his fractions worksheet?

Eventually, they move on. His dad concludes the deer probably won’t be coming back; they’ve most likely returned to the cover of the woods.

#

Wyatt ate sour cream and onion chips from a styrofoam bowl and returned to the basement. However, Erika was not there, so he went back upstairs. He didn’t find her there, either, so he went to the second floor. Nobody had told him he could go up there, but he didn’t think they would care.

His house only had one floor, but it also had a big porch and a fire pit. There were woods all around it, and the land sloped slightly. Their kitchen was big, the living room was carpeted, and there were always soft blankets that his mom got from Costco. They also had a shed with a freezer, where his dad kept all his hunting stuff. Technically, Wyatt’s house wasn’t much smaller than Erika’s. But her house felt massive. There was something dark and womb-like about the upstairs hallway, the way the dark moved in from the walls.

At the end, though, a door was open, and light spilled out. Inside it was Erika.

“Is this your room?” He said.

There was so much. A magenta comforter and matching pillows. A white desk with a laptop and a purple backpack slouched in a chair. Legos, pop-its, and stuffed animals lined the bookshelves. More stuffed animals crowded the bed.

Erika, sitting on the floor, looked up from the iPad.

“Yeah,” she said. “You can stay if you want. I just came up here because there’s so many little kids.”

Wyatt nodded. He walked in and sat next to her. She was watching a video. It was an animation of toilets moving around an empty office building. Men’s heads with wide grins and deep sunk eyes stuck out of the bowls and sang together.

“Is that Skibidi Toilet?” He said.

Erika nodded without looking at him.

“Your parents let you watch it?”

She shrugged. “My stepdad said it’s fine.”

Wyatt narrowed his eyes.

“My mom hates it,” he said.

“It’s not that bad,” Erika didn’t look up.

“It’s not that. She just doesn’t like me on the tablet.”

“At all?”

He shook his head. “No. I can play on weekends.”

Erika frowned and looked back at the video. The toilets were now in an alley, fighting with men who had boomboxes and TVs for heads. One of the toilets lunged at a TV-headed man, grinning, but the man suffocated it with a plunger.

#

It’s around two o’clock that Wyatt starts getting frustrated again. They’ve been out there all day. He wants to go home, watch TV, and have a pop-tart. But he knows that their job will not be over even once they get home. They’ll need to prepare the deer. Wyatt said he’d wanted to help, and he did, but he didn’t think about how long they’d be out here, how ready he’d be to do something else. The boredom is a physical presence in his body. He feels it wriggling and imagines it like worms, hundreds and hundreds of worms. When he was younger, he used to cut worms at the citellum. He didn’t understand then, but now he feels awful about it. He wonders if worms can be ghosts. He wonders if the ghosts of worms have the consciousness to haunt him.

#

The night was heavy, and the world outside didn’t exist. Wyatt stayed in Erika’s room and fought the urge to sleep.

Eventually, Erika got bored, so they grabbed some food from downstairs. On the way, Wyatt looked outside and saw his dad wasn’t there anymore. He looked around and saw him talking to two other men in the kitchen by the garage door. Wyatt didn’t go up to him because he had a plate full of brownie bites and potato skins. His parents usually didn’t let him eat those things.

Back upstairs, they ate, and Erika told him about her school.

“I got the Golden Eagle Award for good grades,” she said. “I got an A in everything.”

Wyatt nodded, balancing his plate in his lap.

“That’s cool. We don’t have that at my school.”

“What do you mean?”

He quickly swallowed his brownie and suddenly realized how dry it was. He wasn’t sure why he’d grabbed so many.

“Like, they don’t give us grades,” he said. “They talk to your parents and stuff about how you’re doing. But they think grades aren’t helpful.”

“But how do you learn anything?” Said Erika.

He shrugged. “I dunno. We still learn stuff, but it’s just different.”

“Well, my grandma and grandpa came to watch me get the award,” she continued.

“Which ones?” He said.

“My mom’s.”

“Oh. I never met them.”

Erika just looked at him. “I know.”

Wyatt frowned. He didn’t like the way she said it. Come to think of it, he didn’t like her scratchy bangs or how she watched Skibidi Toilet or all the purple in her room, either. Then he realized he’d never liked her, but they were the same age, so he’d chosen to hang out with her.

“Do you know why?” She said.

His pulse rose toward his throat. His chest got tight.

“They got in a fight with my parents,” he said.

“Yeah, but do you know what it was about?”

“They didn’t want my mom to marry my dad.”

His parents had explained it to him a long time ago. His grandma and grandpa hadn’t liked his dad, his aunt hadn’t either, and when his parents got married, his mom’s family stopped talking to them. Now things were better; he didn’t see his grandma and grandpa, but his aunt had invited them to this party, all of them, not just him and his mom. And anyway, Wyatt had his grandparents on his dad’s side, and he liked them. For as long as he could remember, he’d known that there was a rift in that part of his family, but it didn’t bother him. He never felt a conspicuous lack, a resentment, all it ever amounted to was morbid curiosity.

Even now, he realized he didn’t feel like he was missing out. He didn’t like his cousin or dislike her. He felt the same way about his aunt and her husband, too. He felt this way about everything in this big house and these strange people.

“Yeah,” said Erika. “Cause your dad’s a pedo.”

Wyatt almost laughed.

“No, he’s not,” he said.

“Do you even know what pedophiles are?”

Wyatt knew what pedophiles were. At sleepovers, he’d watched To Catch a Predator on his friend Damien’s laptop. He’d also gotten talks from both his school and his parents about adults who were inappropriate with kids. Still, he thought about everything his dad had ever done, tried to find something like those men did, but found nothing. All he found was his dad roasting black coffee at five in the morning, cleaning his hunting gear in the evening, and telling Wyatt to make good choices when he dropped him off at school.

Wyatt opened his mouth to respond, but Erika just kept talking.

“He knew your mom since she was a kid. Literally, since she and my mom were in elementary school. He was a friend of our grandpa.”

The brownie bites had left crumbs in his mouth. The chips, too. The soda was an acid fog in his throat. He wished he could throw up.

“That’s not true,” he said.

“It is.”

Wyatt imagined throwing his plate on the carpet, letting the crumbs and greasy bits sink so deep that the floor would never be clean. He thought about his dad standing alone on the porch smoking and his mom with Kennedy in her lap.

“It’s whatever now,” Erika shrugged and grabbed the tablet. “Your mom’s a grownup, so they can’t do anything.”

He stood over her, but she looked at him with her mouth flat and unamused.

“If my dad’s a pedophile, then why is he here?” He said. “Your mom wouldn’t let anybody hurt you, right? So why’d she invite him to your house? He’d never hurt a kid. He’s never hurt me. They’re lying to you.”

She shrugged.

“I’m not saying he’d hurt you,” she said. “It was just weird that he married your mom.”

“But how is it weird?” He said. “You weren’t there, you don’t know. And if it was that bad, your mom wouldn’t invite him here.”

Erika looked away and smirked a little, eyes big.

“Well, she didn’t want to,” she said. “She tried to just invite you and your mom.”

Wyatt narrowed her eyes at Erika. She was weird-looking. Her brown hair reminded him of straw, and she wore a purple pair of cat ears that sat lopsided on her head. He felt a strange superiority to her as if he knew something she didn’t. He knew his mom and dad. She didn’t.

He knew what was true. He knew that his dad tucked him into bed every night. He knew his dad always brought his mom her favorite drink when he stopped for coffee. He knew he was one of the only kids in his class whose parents weren’t divorced.

“They started dating when she was eighteen,” said Erika. “But everyone knows they were together before that.”

Wyatt’s mouth tightened, and his jaw went hard. He thought once more about the party downstairs, the crackling surround-sound system that Erika’s stepdad told everyone about, the picked-over dips, the coolers full of melting ice, gently sweating on the kitchen tile.

“That’s just what they say,” Wyatt looked at her. “You don’t know if it’s true.”

“Have you ever seen any pictures of your mom when she was a kid?” Said Erika.

He scoffed.

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“If you saw any pictures of her, you’d see how young she was. Then you’d see how weird it is.”

It was true; Wyatt knew his mom was younger than his dad. He didn’t know how much, and he’d never cared. Maybe they were different ages, but they were both older than him, old enough to be his parents. But Erika’s ugly words seeped in, and he realized that he’d never actually seen a picture of his mom from when she was a kid. So what? He asked himself the question again and again. So what if there were no pictures of his mom? He knew his mom. He knew his dad. But still, the words sunk even deeper.

Come to think of it, his dad had always seemed more real than his mom. There was evidence of his life—grainy photos of him as a little kid, toddling in diapers, sitting on the bed of his father’s pickup truck. Wyatt knew what he did, how he’d been born in Alabama, worked in construction, and had been hunting white-tailed deer since he was nine.

But his mom, up until now, had felt like she’d simply come from the ether fully formed. She had no past, she just was. All he knew was her in the present. He knew she liked the bird feeder outside the kitchen window, a Christmas gift from his dad. She’d never gotten a taste for alcohol and preferred sparkling grape juice, even on New Year’s Eve.

Wyatt stood up. He felt as if something was hurtling toward the house, a life-ending asteroid or a fleet of hostile alien ships. The ground was immaterial, and he could fall through it any moment.

“I’m going downstairs,” he said and walked away.

#

Long shafts of decaying milkweed sway softly in the breeze. Wyatt and his dad have found a spot to wait, hoping the deer might show, but while his dad watches steadily, he stares at the milkweed. It’s graying, and the dry leaves atrophy into curls. His mom told him that milkweed fibers were used to make the lining of jackets during World War Two.

As he watches them move and scrape against each other, he wonders what his mom is doing right now. She’s probably getting groceries or working on her garden. If she’s done with the chores for the day, she’ll probably read a book.

“Look.”

His dad’s voice pulls him back.

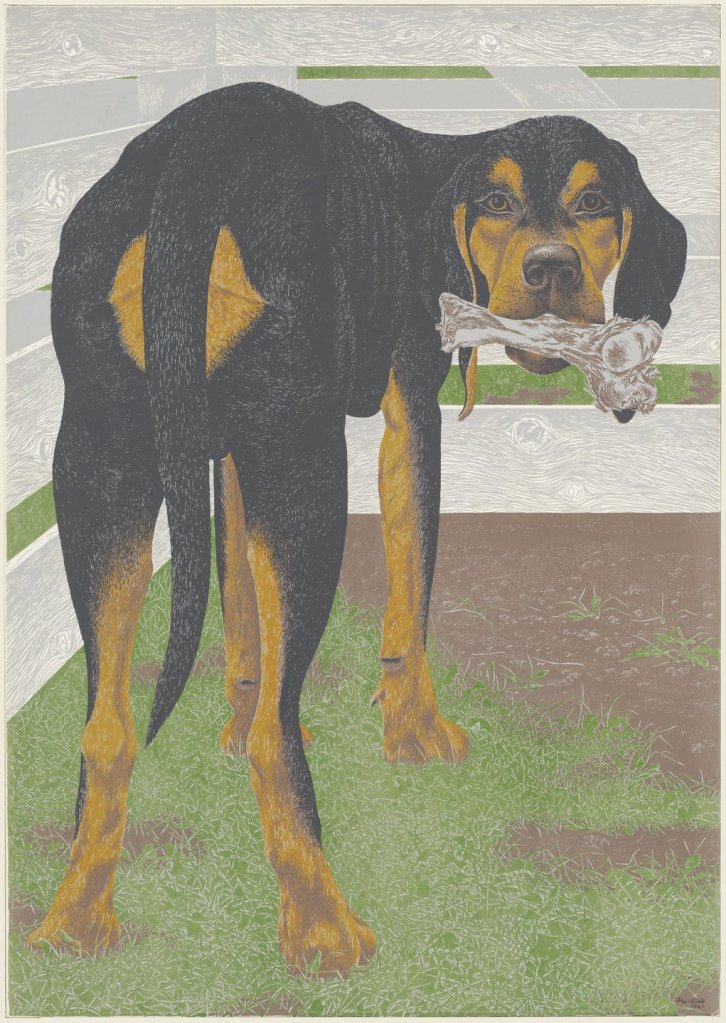

A doe has crept into the small clearing. It’s small and alone, its bent gait between awkward and graceful. Its tail is down, and its wet nose twitches slightly. He hears the slight intake of his dad’s breath and makes himself as still as possible.

From where they’re standing, the doe is at an angle. If they tried to shoot, it would probably hit its haunches or gut. But they can’t move to get a better angle. The doe will hear them. Wyatt wishes they could so they could be done.

They watch for some time, seeing if it’ll turn and give them a clean shot. His dad always talks about the importance of a clean shot. It’s not essential—if you injure it enough, you can, of course, track it down—but a clean shot is more humane and the meat tastes better.

The wind shifts and moves through the clearing. The doe catches their scent and bounds off.

They stand there afterward, and Wyatt’s not sure why.

“It’s a yearling,” his dad says, sighing.

“Can we shoot it?” Wyatt says.

His dad shrugs, then looks back up, eyes narrowed and a slight frown on his face.

“We can,” he says. “I’ve shot one before. Fawns, I leave them alone. But yearlings are fine. They’re old enough to survive on their own.”

Wyatt nods.

One time at school, a girl in his class told Wyatt it was evil that his dad hunted. But the way his dad explains it is that hunting helps keep the population in check. Most of deer’s natural predators don’t do the work they used to, so humans do it instead. What matters more than anything else, his dad says, is that every part of the animal is used, and it’s not just put on a wall as someone’s trophy.

“They’re beautiful animals,” his dad always says. “But they’re not meant for that.”

#

“We should do this again,” Wyatt’s aunt said as she hugged his mom.

His mom quietly agreed. With the floodlight to her back, Wyatt couldn’t see his aunt’s face, only the dark suggestion of it. Words were exchanged. A local fish fry, spring break, things like that. Wyatt let out a breath when he finally got in the car.

“Have a good time?” His dad said as they drove down the dark road.

His mom shrugged.

“Their house is ugly,” she said, and Wyatt could hear the smirk on her face. “And you know it.”

His dad huffed.

“Just because it’s not your style-“

“It’s ugly,” his mom was laughing now, and so was his dad.

Wyatt let his head rest against the seat.

“What about you?” His dad said. “Did you have fun?”

Wyatt saw him lean and glance back, so he shrugged.

“Did you like playing with your cousin?” He continued.

Wyatt looked out the window. He saw pitch black interrupted by street lamps. He thought about Erika’s ugly purple room and the brownie bites that crumbled in his mouth.

“Yeah,” he said.

#

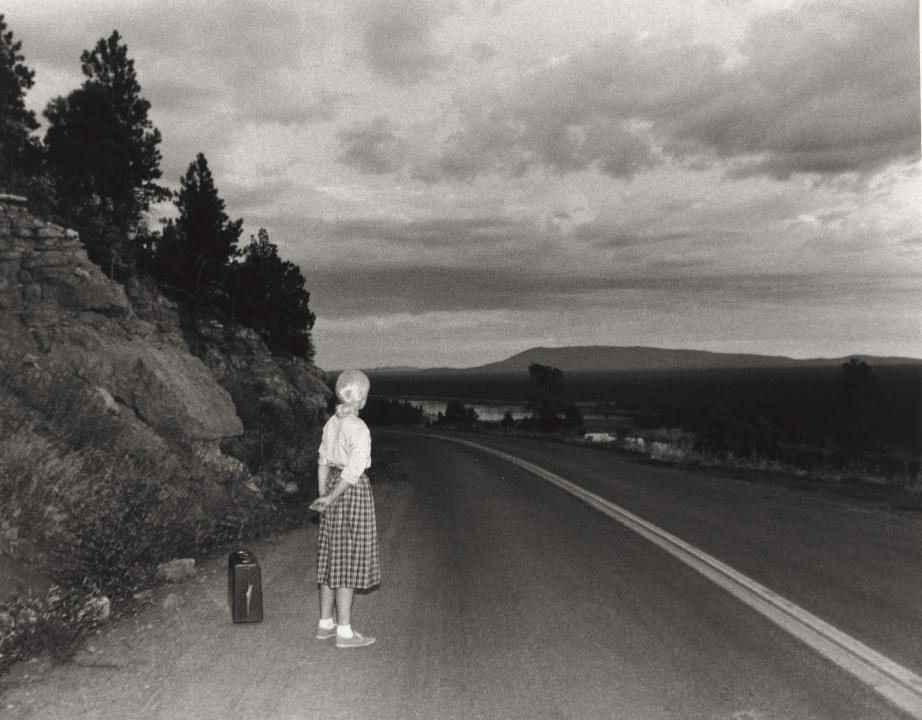

They follow the trail deeper into the woods, so deep that it feels different than the rest of the world. The trees grow denser there, and the way they block out the sun, even though they’re threadbare from the cold, makes it as if they’re not in a forest at all but underground. It reminds Wyatt of a book he read when he was younger about two kids who fall into an underground world where humans ride bats and have translucent skin.

At this point, he has no idea where they’re going. Only his dad sees the trail, and he simply follows. He’s bored and tired and a bit annoyed, but at what, he’s not sure. Eventually, they’ll be done, though. They’ll get the deer, and they’ll go home. His dad will tell his mom all about the things Wyatt did, like noticing the bitten-off grass or the fresh scat, even though it was all his dad in the end. Still, neither his dad nor his mom want to hear about that.

Then they stop. His dad raises his hand, fingers slowly going up one by one. At first, Wyatt thinks they’ve found the doe, but then his dad shrugs off his backpack and quietly goes through it.

“You can sit,” says his dad. “Let’s rest for a second.”

#

Wyatt didn’t dream about anything that night. Nothing existed beyond the walls of his room, not even what he saw out the window. A few times, he woke up and stared at the glow-in-the-dark stars on his ceiling. They had faded, and their strange green light was just a whisper. At some point, he woke up and saw the deep blue morning through his window. Then he heard footsteps and cabinets opening and shutting and figured his dad must be awake. He couldn’t go back to sleep, so he got up.

In the kitchen, his dad was brewing coffee and making eggs.

“Hey,” he said. “Sleep okay?”

Wyatt nodded and sat down at the table. Even though he couldn’t sleep anymore, the residue of it stuck to his eyes. He watched his dad scrape the eggs onto two plates and start grilling sausage links. The air smelled of fat and maple.

“You’re up early,” his dad said when he finally sat at the table.

Even though Wyatt hadn’t asked, his dad passed him a plate of eggs and sausage. They ate in silence. The morning grew brighter, though the sun was not yet up. The eggs became soggy, and the sausages were clammy. Wyatt stared at his plate, fork limp in his right hand.

“You’re not hungry?” His dad said.

He shrugged.

“Do you want cinnamon toast?”

Wyatt perked up.

“Really?”

Cinnamon toast was only for weekends, and it was Sunday, but he’d had so much junk food the night before he didn’t think he’d get it that morning. But his dad shrugged and got to work, toasting two slices of whole-wheat bread, smearing a pat of butter on each, and then sprinkling cinnamon sugar on top.

“Thank you,” Wyatt said as he put the plate before him.

His dad just shrugged again.

But when he took a bite, it was not what he expected. The toast was both dry and soft. The butter was scant, and the cinnamon sugar had too much cinnamon. He ate it anyway because even though his dad acted like it was nothing, it was something—sharing his breakfast, making no fuss when Wyatt didn’t like it, and then making his favorite food instead. It touched something in him that was soft the way a bruise was soft, a softness that was disturbing, like rotting fruit, or seeing your father cry.

“When did you meet Mom?”

His dad looked at him, mouth full of food. Then he swallowed.

“What?” He said.

“When did you meet Mom?”

Wyatt didn’t often see his dad angry. His dad was a tall man with big shoulders and dark eyes that always seemed to squint. But he was not an angry man. He didn’t yell. He never slammed or threw things. Once, Wyatt saw him slam a door, the truck door. It was a long time ago when he was like eight or nine. A lunch lady had commented on Wyatt’s “girl leggings” because they had unicorns on them. His dad had told him and his mom to stay in the car while he talked to the principal.

“You know when I met your mom,” his dad said.

He then returned to his breakfast, using his fork to cut up the links and shuffle the eggs. His shoulders were slightly hunched, and his head was bowed.

“Erika said it was different.”

His dad looked up but didn’t put his fork down.

“Oh yeah? How’d she say it happened?”

As Wyatt tried to put the words together, his account felt puny to his dad’s. Why had he believed Erika? Why hadn’t he questioned her more, asked for details? How could he question what happened when he hadn’t even been there?

The ridiculousness bared itself like a pervert.

“She said you knew Mom when she was a kid,” he heard himself say. “People thought you had…”

What had he done? What was the word for it? Did it even exist?

“What’d they think I did?” His dad cut up the sausage again, then scooped up his eggs and took a hurried bite.

Wyatt looked down at his plate and shrugged. His dad chewed, then took another bite. Then he swallowed, wiped his mouth with a napkin, and leaned back.

“I love your mother,” he said. “What happened between us wasn’t like your cousin said. Nothing wrong ever happened. And there was stuff going on in her family. Stuff your cousin doesn’t know about. That’s it, that’s all there is to it. She shouldn’t have said that to you. I’m sorry.”

His dad resumed eating. He finished his plate, wiped his mouth again, and stood up. He put his plate in the sink and rinsed it. Then he walked away.

#

The doe reappears while they’re sitting, Wyatt staring at the ground while his dad sits across from him, binoculars in hand. It’s how they’ve been since they first came upon the area. Just the two of them, bored but comfortable.

His dad notices it first, as he always does. His face tenses, and he motions for Wyatt to get up. Through the trees, he sees it. Much to his surprise, his dad hands him the rifle.

The doe stands in silence. It’s a silence with weight, a weight that’s almost crushing. Wyatt feels it in his lungs, on the back of his neck. It isn’t even weight as much as a pull, like gravity is stronger there. He remembers when he first learned about black holes, and that’s what he thinks of at that moment.

When he was about eight, he became obsessed with outer space, so his parents bought him a children’s book about it. One page discussed black holes and how their gravity was so strong that not even light could escape. He never told his parents, but it scared him so much that he put the book under his bed and never read it again.

What if there’s a black hole in the center of this clearing? What if the doe is the black hole? He knows the prospect is ridiculous, but it tugs on the pit of his stomach like the moments after his parents tell him, “We need to talk.”

The rifle makes his arms ache. It’s too big for him. He holds it anyway.

Then the doe raises her head and looks behind her. Then she looks forward again, carefully takes a step, and then another.

“Now?” He whispers.

Behind him, his dad’s breath is near-silent but shaking.

“No,” he says. “No, wait a sec.”

The doe lowers her head again and grazes. Now Wyatt is impatient. The bones in his hand itch.

“What about now?”

Though he can’t see him, he knows his dad is shaking his head.

“But-“

“It’s not a clean shot.”

Rage blooms in his stomach. They’ve spent all day out there, looking at crushed grass and scat, barely even speaking, and for what? This is their chance.

The doe raises her head and takes another step. She has big, black eyes, black holes for eyes. The wind rustles against the back of Wyatt’s neck.

“We can’t,” his dad says.

Wyatt breathes out his nose, lips pressed together. His dad places a hand on the rifle and gently pushes it down.

“Just trust me,” he says. “Let it go.”

So they stand together and let it go.

Gabriela Gorgas is a writer from Ohio whose work has appeared in The End , Muumuu House, and Default Blog. She can also be found on Instagram @gabriela.gorgas and on Substack at gabrielagorgas.substack.com.