by Maud Bougerol

“A book about how difficult it is to change, why we don’t want to, and what is going on in our brain. A book can be about more than one thing, like a kaleidoscope, it can have many things that coalesce into one thing, different strands of a story, the attempt to do several, many, more than one thing at a time, since a book is kept together by its binding. A book like a shopping mart, all the selections. A book that does only one thing, one thing at a time. A book that even the hardest of men would read. A book that is a game.” (7)

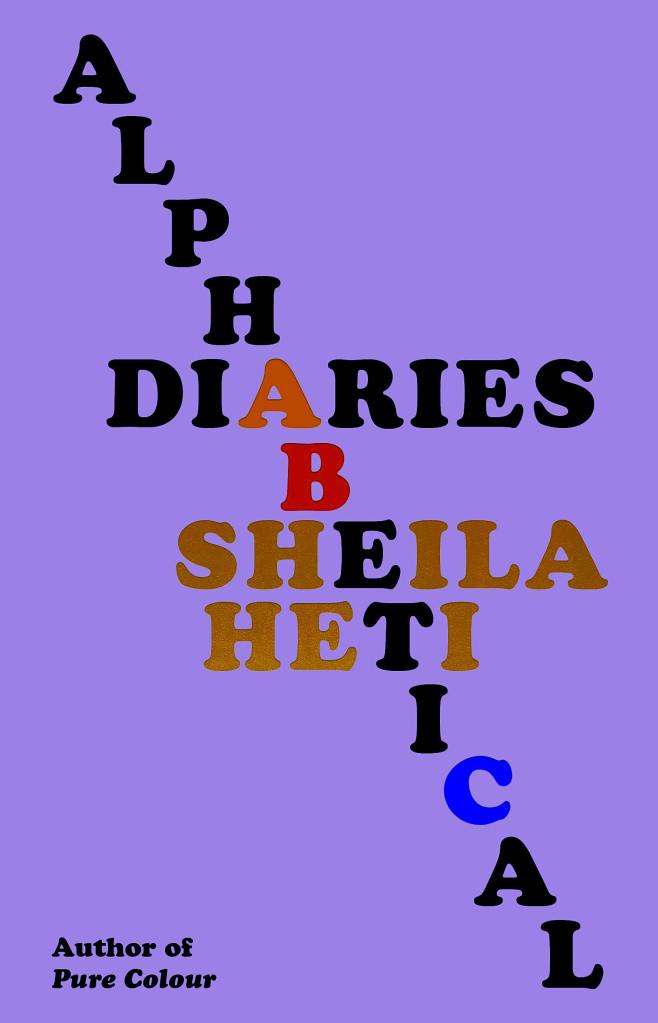

Few authors state their literary project as compellingly as Sheila Heti does in these opening lines of Alphabetical Diaries. In some ways, this book is indeed an object that “attempt[s] to do several, many, more than one thing at a time”, all the while maintaining a demanding structure that calls the Oulipian experiments to mind.

Sheila Heti selected sentences from ten years of her diary entries and arranged them according to their first letter. The book is divided into twenty-six chapters, one for each letter of the alphabet. She then applied this system to the following letters and words. Heti didn’t just organize the sentences, though—she heavily edited the material through picking and choosing, without, however, modifying the sentences themselves. The result is an achronological, hybrid book, part diary, part memoir, part (auto)fiction, a form of experimental prose that teeters on the edge of poetry and can be read in many different ways, granting a great deal of freedom to the reader.

Those who are used to Sheila Heti’s style and the themes she developed in her previous immensely popular novels How Should a Person Be? (2010), Motherhood (2018) and Pure Color (2022) will easily recognize her delightfully raw and elegantly caressing writing, as well as her interest in love, sex, friendship, family, self-discovery and art—and the way these elements, always entangled, dialogue with writing and creation. Reading Alphabetical Diaries is thus a both strange and familiar experience.

The reader’s relationship to this text was a significant part of the discussion between Adam Biles, literary director at the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, and Sheila Heti during the event organized to celebrate the book in May 2024. To Biles’s question on how it should or could be read, Heti explained that she had purposefully crafted a “relentless and exhausting” experience for the reader. To her, the varying length of the chapters—Y being obviously longer than Z for example—as well as the short breaks between them, compose the driving force of the reading experience.

As the reader drifts back and forth between sentences that sometimes seem related—although they know they probably aren’t—and sometimes appear completely antithetical, they experience many of the facets of a woman’s life with varying degrees of importance, all put under the microscope and the unreliable gaze of the ‘I’. No wonder the ‘I’ chapter, which acts as a pull, a “draw” to reuse Biles’s words, is one of the longest in the book and the most complex. It allows Heti to exploit the metatextual possibilities of the text and reflect on her “kaleidoscopic” experience and identity, not just as the author of these diary entries, but as a writer of generically and structurally complex and hybrid texts, thus justifying the plural in the title of the book:

“I am finished with my book, but my book is not finished with me” (51-52)

Alphabetical Diaries, which bears in its intimate material the mark of disclosure, transparency and fearlessness, is Heti’s radical experimentation with her own writing. She innovates and creates a form of fiction that questions its role and inception in the 21st century. French philosopher Jean-Marie Schaeffer called fiction “an emerging reality”. By blurring the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, Sheila Heti offers the reader the opportunity to simultaneously enjoy the performance of the real she is putting on for them and to take a look at her pulling the strings behind the curtain.

I have read the book three times, in three different ways. First, one chapter daily. Second, picking and choosing sentences at random in each section. Finally, from cover to cover, over the course of a few days. If the first reading sold me on the project, the last one entranced me completely. In the game of choose-your-own-reading offered by Heti, every possibility births a meditative reading experience that calls for several other readings to encounter the text fully and uncompromisingly.

Read all the way through, Alphabetical Diaries is challenging. This “decontextualized chaos” of sentences—as Heti put it in her interview with Biles—demands the reader either take an active part in the experience by reconstructing networks of meaning through recognizable elements—pseudonyms, places, dates, events, etc.—echoed from one chapter to the next, or to let go completely and relinquish control to the poetry of the book. Indeed, it is a text that “comes in waves like stream of consciousness” (14) but in a constrained form, playing with pace—accelerations and decelerations—, recurring motifs, and language.

The division into chapters isn’t a mere gimmick, as Heti seemingly ascribes a different tone to each. For example, while the D and G chapters explore the imperative, H and W delve into the interrogative. She sets up delightfully dizzying juxtapositions of short sentences, alternating personal reflections, astute descriptions of the characters in her life, pieces of advice, and more philosophical reflections on life, love and loss.

Like mantras and prayers, the text of Alphabetical Diaries demands an involvement that is both intellectual and physical. The reader commits their body to its labyrinthine nature. Just as an invocation may take on different connotations depending on the way it is spoken, Heti’s text spurs different meanings according to the way it is read. Much like the opening lines of the A chapter, the unformatted blocks of text that make up the book can be taken apart, read separately, or in different sequences—or, as Heti intended, read all the way through. Each approach yields distinct meanings and experiences that evolve from one sitting to the next.

This fertile ambiguity blossoms in the use of the ‘you’, a necessary distancing tool in Heti’s journey of self-examination that the reader can’t help but feel exhorted by:

“You need so much stimulation to feel so little.” (162)

Sometimes humorous, sometimes heartbreaking, Alphabetical Diaries is the book every writer, regardless of their ambition, should read at least once. Heti manages to encompass, in just a few words, the ambivalence of the human condition in a hyperconnected world that makes us all hyperaware, hypersensitive, lost, isolated and lonely, as demonstrated by the longest sentence in the book:

“Write the book that—when a person is taking a thirteen-hour train to a city they’re not sure they want to go to, to stay with a man they’re not sure they can stay with, leaving behind their marriage on New Year’ Day, nervous about having enticed a new man too much, and having listened to the mixtape made by their ex-husband, which is so heartbreaking, so now it’s finally clear what he is feeling and the things he has been thinking, and her heart is aching, and maybe she will go back to him but she doesn’t want to yet, and this lostness—this feeling like she just wants someone to take her heart in their hands and lay it in a bowl of warm blood and lap it in the blood with their hands, just wash their heart gently, polishing it like a pearl so it will come out thicker, shinier, and ready to be put back in the coffin of her chest, so she can step off the train like someone who’s had a good upbringing and has been loved, who can look herself square in the eye without deceit, and can look everyone square in the eye without deceit, so they are understood by her and she by them, like a fresh rain and sudden blooming—write the book that this person would choose.” (158)

It's a book that exhorts, excites, and consoles, the way only the best books do.

Maud Bougerol is an associate professor of contemporary American literature. She reads, writes and teaches in France, dividing her time between Paris and Marseilles. More of her writing can be found at dancingonthepalimpsest.substack.com.

Leave a comment