Brothers & Sisters—the world works in mysterious ways, indeed. I could tell you how I came to discover The Last Panther of the Ozarks, but it does not matter; it happened like anything else happens: by mere chance, pure accident, random consequence. This is how things go.

One day you’re on one path, the next day you’re on another—hellbent to wild country. The strange thing is, you had seen and heard this place before, in your own mind some time prior, in both dreams and in waking life. It is not a strange land; you nearly know it already—its vistas and customs, its lore and language. It is a vision and song combined. You are a welcome pilgrim.

Brothers & Sisters—this is where I found myself. I will tell you now some things I saw: breathing ghosts of the river deltas; a country gentleman of French ancestry on horseback; a woman on a raft bringing milk, cornmeal, and candles; Cajun balladeers; Benedictine monks asleep in canoes; a preacher carving his sermon with a butterfly knife; bluesmen in the barbershop singing their songs of sex and death; an outlaw with a mandolin leading a funeral procession; cottonmouths sucking the blood out of children in their sleep; levee builders; dam builders; men and women in union as if giving themselves to a Moon-God; and Death himself took many forms: he was a long black train; he was a bird; he was a riverboat captain who knew your mother’s maiden name; he was a pilot who handed you his silk scarf; he spoke a dialect of Latin and Creole and sang in the high lonesome tenor; he wore a leisure suit and always had money for the jukebox.

Time ran like a camera on fire. I brought back three souvenirs: an arrowhead, a feather, an eyelash.

⤅

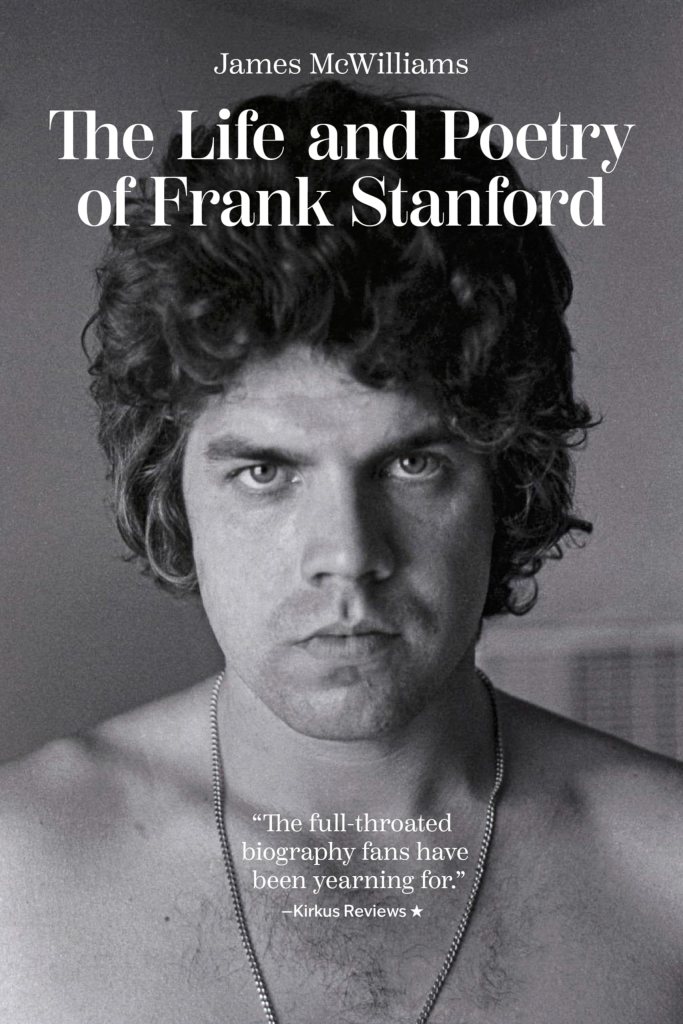

WT: As much as I’d love to try to ask my questions in prose poem form, I don’t have the chops to pull it off—so I’ll switch to a more straightforward delivery. First of all, congratulations on the publication; this has been a long time coming for the already initiated to the work and world of Frank Stanford. What does Stanford’s work mean to you and how different is your relationship to it after eight years of research?

JM: I first discovered Frank Stanford’s epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You in 2000, just after Lost Roads published the second edition. Reading it felt like I’d caught a rogue wave during a fever dream in the middle of some mythical ocean, rode it like a banshee until it dumped me in some wayward Delta cotton patch, where I woke up naked and disoriented, panthers and hawks circling. Changed. That’s about the best I can do for telling you what Frank’s work initially meant to me. Over the last two decades, especially during the research and writing of the biography, I’ve recovered some of my balance, knocked the shine off a few Stanfordian myths, and partially demystified the fumarole that fueled Frank’s poetry. But–and this is critical–knowledge has not ruined experience (I’m an historian, and we can make anything boring.). Even though I have probed the depths of Frank’s life and work as much as I can imagine anyone probing into it, reading his poems still transports me back to that ocean. I still lose myself on that crazy ride. The facts of Stanford’s life have done nothing to diminish the magic of the poetry. Perhaps they have enhanced it.

WT: You write in the introduction: “While Melville had Moby-Dick, Whitman had Leaves of Grass, and Ginsberg had Howl—and Frank knew each of these works well—Frank Stanford had The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You.” We’re nearly fifty years since Stanford took his life; fifty years of legacy and reverence that has included essays by C.D. Wright, Forrest Gander’s (Wright’s husband) novel As a Friend, and songs by both The Indigo Girls (“Three Hits”) and Lucinda Williams (“Pineola”). It’s been ten years since Copper Canyon Press published What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford. Despite all of this, Stanford remains absent from the American literary canon. I have more than a few friends I’ve connected with via Stanford’s work, but us “devoted disciples not/to be denied” (Leon Stokesbury) are few and far between compared to those of Melville, Whitman, and Ginsburg. Is there a place for Stanford among this company, or is he forever destined for the underground?

JM: You think I spent nearly a decade of my life researching and writing and almost losing my mind (twice) over Frank Stanford thinking he would be “forever destined for the underground”?!!!!! Of course, you have asked the essential question about Stanford’s legacy. It’s a very Melville kind of question (the guy died poor and generally unknown). Putting aside why Frank has been downplayed by those who determine canonical status (aside from saying that being from the South never helps), what drives me to relentlessly promote Stanford’s life, work, and legacy is that his ear for the multiplicities and nuances of American vernaculars was simply unparalleled. He loved how people talked–their accents and linguistic quirks, their odd phrases and mispronunciations– and he took an almost anthropological approach to lingua francas that were off the grid, teeming with lust, and devoid of decorum. Frank listened to his world with the rarest generosity, and he listened much more carefully than it has yet to listen to him. And who did he best hear? The misfits, the outcasts, the holy fools, the impulsive and the downtrodden. He ushered their crude and sometimes violent idiom into eloquence, often in defiance of the more conventional language of authority and conformity, which he loathed and sometimes mocked. Every reader I introduce Frank to is astonished that they are just now learning about this poet–I actually keep a list of their responses. That tells you something. Is there a place for Stanford? Hell yes there is. I envision it atop an ancient column rising into the sky from a patch of woods in Arkansas or Mississippi, a pedestal with a panopticonal view of the world, awaiting its poet.

WT: You not only spent time with Stanford’s papers at Yale, but constructed something of your own archive of unpublished pieces, scraps, and ephemera, as well. He left behind a staggering amount of work—he was always writing and revising. What did you discover about Stanford’s process while researching?

JM: A lot, but two qualities stand out. The first is that Frank had a fierce work ethic that reflected an equally fierce ambition to publish in the leading poetry journals. There’s a tendency to romanticize Frank as a poet whose talent was such that he could toss off brilliance on the wing, flying from one escapade to the next, only pausing to jot down poetic genius. Not so. He worked for hours on end, going over and over and over poems, reading them aloud to himself and others, until he got them where he wanted them. All nighters were common for him. The poem “Death and the Arkansas River” took him a year to write. CD Wright remarked that he was the hardest working artist she ever knew. Frank was, in essence, workmanlike. He once said that his attention span was too good–he could lose himself for hours without noticing the outside world. And this segues nicely into the second notable feature about his process: he liked to have a slightly altered consciousness when writing. Not on drugs, which he never took, but more so slightly drunk or deeply sleep addled. He hated when he felt like he was sitting down to write a poem because the result would sound like someone sat down to write a poem. This is why he never really warmed to the seminar or workshop approach to writing poems. Friends and lovers remember him in the zone when he was a little rattled, disheveled, a bit out of time, out of his mind. The people closest to him also remembered that a great source of frustration for Frank was that he literally could not keep up with his ideas. He could not jot them down fast enough. The engine of his inspiration outpaced his ability to write it down.

WT: What is the role of the biographer? How did you approach defining your writing voice for this project in particular?

I’m no authority on biographies. I’d never before written one and swore them off while I wrote. Since finishing my book, I’ve read a half-dozen literary biographies, and have lots of thoughts about them (having now done one), and so I think I can answer your question with a modest amount of half-assed expertise at best. The answer involves achieving two seemingly opposite goals at once. As I went woolgathering for the details–and I believe the biographer must be a certifiable nut about gathering details, I cannot stress this enough– I wanted to keep an emotional distance from Frank while also experiencing his life with the deepest intimacy and empathy imaginable. This can be done. We do it in personal relationships all the time. Sometimes our friend, partner, lover needs us to be detached and objective and full of wisdom and at other times they need us to crawl into the pit with them and gnash our teeth and howl. A good relationship knows when to do what. Maybe the same holds true for the biographer. As for voice, well, once I gathered the material, once I talked to everyone I could talk to, once I interviewed everyone including the frickin lawn boy who cuts Fank’s yard, I laid it all out and said to myself, “this story is yours to fuck up; if you can avoid fucking it up you might just have a heller of a book.”

WT: The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You is currently out of print—but you’re working on an annotated edition (very much looking forward to that). What does the future of Frank Stanford scholarship look like?

JM: It’s actually not annotated. I did annotate it, but then realized this was a bad idea. The annotations overwhelmed the poem. So, a five-month error. But the poem will have over 1000 corrections, as well as around 200 missing lines added. There’s an intro and plot summaries, and an essay on the history of the poem by my co-editor. A.P. Walton. James Joyce, after writing Ulysses, said that the depth of allusions and references in his book would “keep the professors busy for centuries.” I think the same holds true for Stanford.

Wes Tirey is a multidisciplinary artist and musician. He has put out incredible music for the better part of the past two decades. His most recent album, Wes Tirey Sings Selected Works Of Billy The Kid, puts the poems of Michael Ondaatje’s Collected Works of Billy The Kid to music. (Out now on one of our favorite labels, Sun Cru)

James McWilliams is an author, professor and historian currently at Texas State University. His work has appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review, Oxford American, The Paris Review online, The New Yorker, and Harper’s. He is currently working on a book about the poet Everette Maddox.