The cat didn’t die the first time. I thought it was dead, so I let go, but it made a rasping noise and tried to get up. I strangled it again but with the same result. It took me another two tries before I finally killed it, and by then, it wasn’t fun anymore.

Afterward, I sat on my thighs and panted. The trees around me made soft noises and the wind came through. Everything felt like an oven. I stayed in the clearing for what felt like several minutes but was probably just a few seconds. Mosquitos buzzed next to my ear. The honeysuckles, on the edge of blooming, gave an odor that was both sweet and putrid. I got up.

I put the body in a plastic bag and threw it in a ravine. Then I walked home.

The walk home was pleasant. It had rained recently, and the air was flush with the soft smells of spring, of pollen and gasoline. When I reached the neighborhood, kids rode their bikes around the street. Adults stood on driveways and talked, beers sweating in their hands. Everybody looked the same; red-faced, cornfed, and blonde—like me.

At home, my mother was making pesto chicken and pasta, and my brother was sitting on the carpet playing Minecraft. I changed the TV, but he got up and tried to wrestle the remote away from me, so I hit him with it. He crumbled to the floor and cried, and my mother slammed down her knife and told me to stop. She sent me to my room until my dad got home and said she would talk to him about my behavior. But when he got home, she didn’t. I sat at dinner and listened to them talk about taking us to a water park. I waited for the remote to be brought up, but it wasn’t.

“What did you do all day?” My dad asked.

I looked up, in the process of licking pesto out from under my fingernails.

“You know how Libby is,” my mother said with a tight smile. “She just did her exploring.”

We went to a barbecue at our next door neighbor’s place. It was the middle of a heat wave. I sat in the living room, where it was cool and dark, watching TV with the rest of the kids. My fingers were oily from salt and vinegar chips. I had red welts from clenching one sweaty thigh over the other. I made it through two episodes of Adventure Time before I put my plate down and went upstairs without being noticed.

All the houses here had more or less the same floor plan. I knew to find the master bedroom at the very end of the hall. I crept inside and found a defunct foot bath, herbal supplements, orthopedic pillows. A shrine of comfort to the middle-aged body. The bed was unmade and all the blinds were down, but the sun got in anyway. In one of the drawers, I found sports magazines and a set of sex dice. I rolled to see what I got.

Suck toes.

“You’re not supposed to be in here.”

I turned to find my brother and his friend Damon standing in the doorway, arm-to-arm and motionless.

I approached them and stared down as if I weren’t only a few inches taller. I was small for fourteen.

“What are you going to do?”

Damon blinked. He had big, watery eyes, made even bigger by the glasses that wrapped around his head, the kind babies wore. My brother was the only kid in fourth grade who didn’t tease him for them.

I looked at Damon, “Do you want some pop?”

He nodded thoughtlessly. His parents had him on a special diet that didn’t allow carbonated drinks, not even mineral water. Our parents allowed pop, but just one cup a day. So I got him a big cup of store-brand lemon-lime and some Dr. Pepper for my brother. I also guzzled lukewarm Coca-Cola, finishing it in two gulps. We watched more TV. Nobody said a word.

I went looking for more cats. It was the fifth day of the heat wave. The concrete was neon, the air slippery. I lasted five minutes before I went back inside. My brother was in the living room, but the TV was off and he had the Switch. I figured my mother was still working in the basement. I grabbed a cherry popsicle and turned the TV to a documentary about the Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. I sucked desperately until it left a red ring around my mouth. I sat with my legs wide and uncaring. When I got bored, I went upstairs, peeled my clothes off, and crawled beneath my covers. I put my hand between my legs and masturbated, breathing heavily like an animal in the dark.

Sometimes I get this restlessness. I don’t know how else to describe it. It’s like there’s something moving around inside me, and it won’t stop unless I do something drastic. The first time I remember feeling it, I must’ve been five or six. I was in the backyard by myself. Then it came, a strange awareness of my body, of the space around it, of its need to do something.

There was a bird’s nest in one of the trees that my mother was obsessed with. Curious, I took a little blue egg and crushed it between my fingers. I watched blood and yolk and soft bone drip onto the dirt, then I smeared it around until it turned into a sticky kind of mud, which I rolled between my palms and made into balls.

That same restlessness came to me in the morning, while I was eating cereal on the kitchen island, picking out the freeze-dried marshmallows so I could have them first. The sun hadn’t risen above the trees yet, but the air was already heavy. My mother came up from the basement to make sure I’d taken my medicine. I assured her that I had, but she counted the pills, just in case. Then she reminded me I had an appointment with Dr. Abrams next week. Her interruption only made the restlessness worse. I tried to soothe it. I watched traffic cam footage of fatal accidents and cartel shootings on my phone. I picked at the dirt between my fingernails. I tried to read a book. I spent an hour watching a Netflix drama about Norwegian teenagers. But I still felt it.

I woke up from a nap and found my brother and Damon playing Fortnite. Neither of them looked at me.

The longer the break crept on, the worse the restlessness got. I went out in search of more cats, but the heat made me nauseous, so I went back in.

I drank a glass of whole milk, all in one gulp, and stared at the back of Damon’s head. It had a funny shape. His face was weirdly flat, chinless, and his mouth always hung open a little, even when he was eating. I once asked my mother if he was retarded, but she just told me not to use that word.

On Wednesday, there was a break in the heatwave, 102 degrees to 78, followed by a burst of rain. The neighborhood was alive with kids who had too much energy and nowhere to go. I went for a walk, stepping on worms dredged up by the rain and watching for stray cats. Some boys asked if I wanted to hang out. We were friends in the way that you hang out when there’s nobody else around, or sit together at lunch but don’t talk.

We gathered in one boy, Joshua’s, basement. It was cool and poorly lit, the walls bare, cabling exposed, cardboard boxes stacked high. They were still renovating it. He turned on the TV and searched for the weirdest videos he could find. We did this sometimes, getting together and watching things like 1 Guy 1 Jar, or whatever was trending on Liveleak, just to see how much we could bear.

“Have you seen Mr. Hands?” Said Joshua.

“Is that the one where the guy fucks the horse?” Said one of his friends.

“He gets fucked by the horse,” someone corrected.

We all looked at each other. We’d already seen Mr. Hands.

“Didn’t he die after that?” Asked the only other girl, someone’s girlfriend.

Nobody answered her.

I sat on the far right side of the couch, next to another boy, James. He made me feel funny. I guess you could call it a crush. I was never bad at talking to people. They didn’t intimidate me, friends, teachers, or parents. But around James my head got fuzzy, I choked on my own tongue, and every word I got out sounded stupid. He told me I was quiet, but I knew this was a different quiet, not a quiet that intimidated people. It was a quiet that went the other way around.

He was sixteen but looked like a man. He had a buzzcut and a face that was sharp and slightly feminine. He was in JROTC, and he worked out. You could see it in his arms and his chest. The other boys worked out too, but with no real goals or discipline, more like a wanton display of masculinity. We were friends, sort of. We talked from time to time. Sometimes I thought he liked me, he’d even suggested we hang out just the two of us. He asked for my number and said he’d text me, but he never did. I remember going to the woods and trying to kill a squirrel after that. I didn’t succeed.

Eventually, Joshua put on some porn his dad had rented from their streaming service. Who rents porn? He said, and we all laughed.

The video was about a woman who had sex with a pizza guy. The woman had bleached hair and hard-looking breasts. The pizza guy was bald and somehow short, fat, and muscular all at the same time. They changed positions frequently, each one more acrobatic than the last. They made animal noises and said things so vulgar they weren’t even erotic. Sometimes the camera zoomed in on the genitals, which looked like an alien flower.

Afterward, we sat in confused silence, our bodies limber and aching. The only sound was that of our own breathing, and even that was sexually charged by then.

We watched a few more videos, but eventually, we all excused ourselves, shameful.

I went home and masturbated again. I thought of the video. I thought of James. I thought of the last cat I’d killed. I thought about its tiny neck, about the desperate noises it made beneath me, almost like that man in the video.

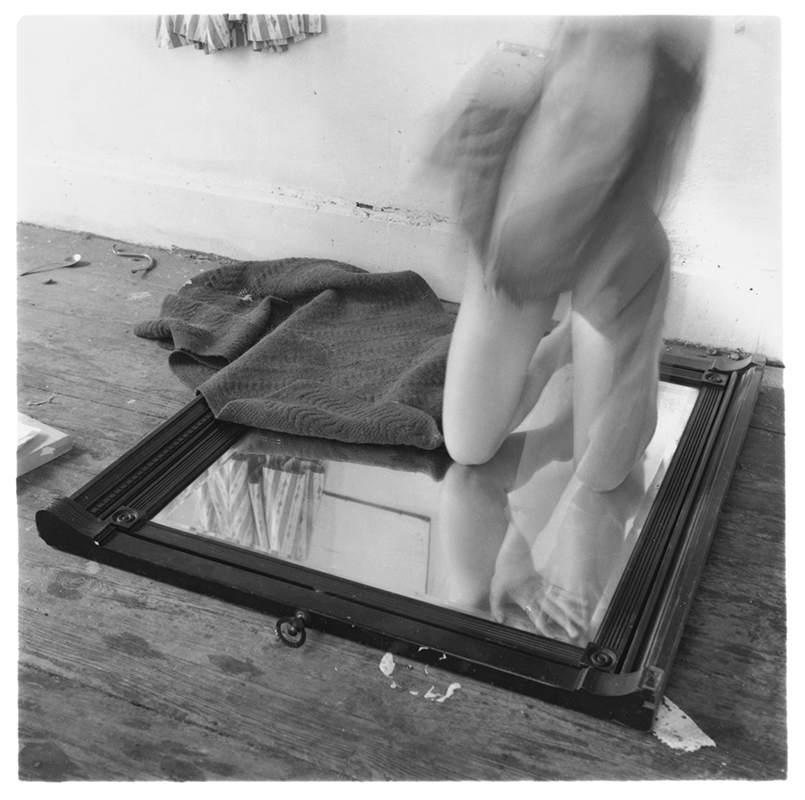

Francesca Woodman - [untitled]- Providence, Rhode Island 1975-1976

I went for another walk on Thursday. It was still mid-morning, early enough that the heat wasn’t stifling yet. There were a few kids out. I passed a teenage girl whom I’d never talked to sitting in a lawn chair, texting while her little sister went up and down the driveway on a tricycle. At another house, two boys a bit younger than me played soccer.

I approached the exit to the main road. Our neighborhood was nowhere in particular. Once you got onto the main road, it was just a UDF, and then flat meadows and the occasional cluster of trees stretched in every direction. About fifteen minutes north, there was a shopping center. On the way, the only building you would pass was a non-denominational church.

A skinny couple walked with their kids in a double stroller. They waved at me and I waved back. As I looped around and headed toward my house, I passed James’ house, and found him in the driveway. He was playing basketball by himself, but when he saw me, he stopped.

“Hey, Libby.”

I held my hand over my eyes to shield them from the sun. “Hey.”

“You just out on a walk?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s nice.”

We stared at each other. Across the street, a beefy man rode up and down his lawn on a mower.

“You should toss me the ball,” I said.

He did that, and I caught it. I then threw it back. We continued that for some time. I felt like he was on the verge of saying something, because he kept on looking away from me, but not like he’d rather be somewhere else. Eventually, he told me that he and his friends were going to a soft-serve place one township over. I knew that place because the parking lot overflowed with cars in the summer. A few years ago, a kid was hit by a car that had been backing out. He had a broken leg but besides that he was fine.

“That could be fun,” I said.

“Have you ever been?”

I shook my head. “No. But we’ve driven past it a bunch.”

“It’s really good,” he tossed me the ball. “My girlfriend’s going too. I think you guys would get along.”

I caught it. The leather was now hard and pimply against my sweaty palms. The sun hung heavier than ever. Even my hair was heavy, lank against my neck. The way my ponytail pulled on my temples gave me a headache.

“Yeah, I’ll see,” I said, glancing away. “I should get home. Just text me.”

I tossed the ball back to him and he nodded.

“Will do.”

But he didn’t text me. I spent the night on my phone, watching for his name to appear on my screen, feeling a phantom buzz in my palms, but the message never came. I slept until noon on Friday and found the house empty.

Outside my brother and Damon were playing basketball in our driveway. My brother was attempting all the things he’d seen on TV, spinning while trying to shoot, passing the ball between his legs as he dribbled, throwing it backward. Damon watched. When my brother passed the ball to him, he tried to dribble. His free hand hung at his side. The ball bounced out of his grasp, and he chased it lamely down the driveway.

“Where’s Mom?” I said.

“She went out,” said my brother.

“Oh.”

I looked around. The streets were dead. Not even one guy on a lawnmower. Once again, that feeling, that unbearable stillness, presented itself to me, like a yawn growing wider and wider, taking me into its maw. I needed something to do, and I needed it now.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

My brother looked at Damon and shrugged.

“Do you want to play hide and seek?”

“Where?”

I looked away. “I dunno. The woods?”

We weren’t supposed to go there, even though I went all the time. It felt like the adults were at war with that forest. Sometimes people talked about cutting it down and building a playground, but it never happened.

My brother got this look on his face; he frowned, narrowed his eyes, and I wondered, without panic, if he knew what I was doing, even though I didn’t know what I was doing.

“I don’t think we can go there by ourselves.”

“You wouldn’t be by yourselves. You’d be with me.”

The boys looked at each other and shrugged. “Okay.”

It was one of those days where the sky was white, almost blinding, and the air wasn’t just hot but humid, especially the deeper you walked into the woods, where the ground was still wet from the previous rain. The sun beat against the back of my neck, a distant but angry eye. The longer we walked, the taller the weeds grew. They pulled at our legs and left sharp kisses. I wasn’t sure how long to keep walking. I actually wasn’t sure what I was doing at all. At one point I thought about turning around. Maybe our mom was already back. Maybe she would notice we were gone.

But then I felt it again. That buzz beneath my skin, that swollen feeling, like arousal. I heard my blood rushing in my ears and I felt a little dizzy, but in a good way. The nervousness lifted and turned into an inexplicable clearness. Suddenly I felt very calm, but a new kind of calm.

“Who’s it?” Said Damon.

“Why don’t you be it?” I said to my brother.

“Why do I have to be it?”

I shrugged.

“Whoever gets caught first has to be it next,” I said as if that was some kind of consolation.

So he turned around, covered his eyes, and began counting back from twenty.

I looked at Damon and motioned for him to follow me. He stared at my brother but did as I said. We snuck through the brush, our feet moving lightly. I tried to remember how to get to my clearing, the same one where I took the stray cats.

“Eighteen, seventeen,” my brother said.

Not far away there was a creek. A long time ago, possibly before humans had even existed, it had been a river. But over time, it had thinned and thinned, until it didn’t even make noise most of the time, and in the summer it sometimes dried up entirely. Its mark on the earth was still left though, a small gorge where the ground dropped steeply, exposing siltstone, animal burrows, and tree roots.

I grabbed Damon by the arm. We walked sideways down the slope, careful not to slip.

“Fourteen, thirteen…”

Our feet splashed in the water. The creek was higher than usual. It must’ve been the rain. The mud sucked at our feet, but my whole body was throbbing. I felt an urgency I’d never known before, I was too excited to stop. We crossed it and returned to land. Our shoes were soaked, but Damon said nothing. We ran further.

“Eleven, ten, nine…”

I’m not sure how far we made it, but finally, I found the clearing. The honeysuckle bushes had bloomed, obscuring the vision of anyone outside the clearing; if we were quiet, we might not be seen.

We stopped, I crouched down behind a tree and took Damon with me. My brother’s voice was distant. Besides that, it was birds, the chittering of insects, and our own unsteady breathing. We were so close. I felt the soft hairs on his skinny arms against my own. He was so small.

I’d seen Damon plenty of times, but this was the first time I’d ever really looked at him. He was so pale. His skin had a gray tint to it. Even though his eyes looked huge beneath his glasses, it didn’t seem like he actually saw anything. It didn’t seem like he was even with me; it was like there was nothing there. He was background noise, as insignificant as the rotting leaves under our feet.

This was my chance, I realized. All I had to do was push him. I wasn’t much bigger, but if I got my hands around his throat fast enough he wouldn’t be able to say anything. I knew from the cats that it took longer to suffocate someone than it seemed. But we were far enough from my brother. And even if he did get near us before then, I’d be able to hear him coming. If Damon was unconscious, I could say he’d passed out from the heat, or something like that. I just had to do it.

A bird took flight above us. Damon looked up, gaping. I stared at his head. It looked soft and helpless; it seemed impossible that it wouldn’t immediately give beneath the slightest pressure. He was still crouched. I just had to stand up, push him down, and get my hands around his neck.

But I didn’t. I don’t know why. I crouched next to him, the sun moving closer, the air heavy and pink from the honeysuckles. About three minutes later, my brother found us.

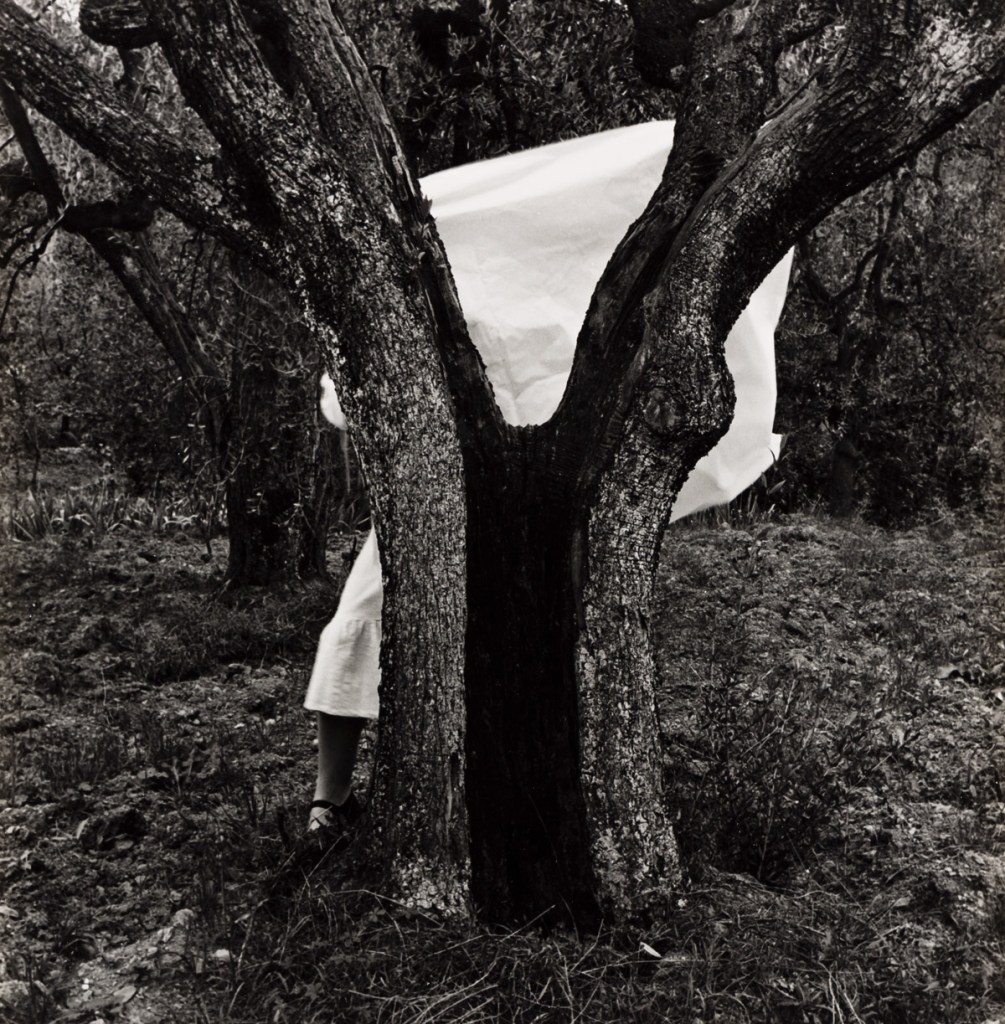

Francesca Woodman - Self-portrait behind tree - 1977-1978

On Sunday we went out to eat. My parents, stingy as they were, had no specific reason for why we were going, which made me suspicious. My first thought was that they’d found out I’d taken my brother and Damon to the woods. Maybe they were about to announce that they were finally sending me to inpatient treatment like they’d been threatening. Or maybe it was some other kind of bad news. Maybe they were getting a divorce. I whispered it to my brother, and he told me to shut up and swatted at my arm, so I grabbed him by the wrist and twisted it back until he screamed. Our dad stopped the car and threatened to turn around. But I apologized so he kept driving. By the time we were at our table, my brother seemed to have forgotten the incident entirely and showed me a gif of a cartoon duck dancing to a Nicki Minaj song.

They let us choose an appetizer and have pop, which further heightened my suspicions because they never let us do both. I was silent most of the dinner. I ordered a Sprite and sucked until my stomach was distended. I didn’t touch the egg rolls.

Everything felt wrong in there. It was still daylight outside, but the windows were tinted to keep the sun out, and all the lights were dim. This ambient harp music played on loop. I didn’t like it. Around us were soft conversations, forks clinking against plates, food ground between teeth. I stared at the other people, the obese families, the retired couples, the teenagers on charmless double dates.

On the ride home, my mom mentioned that my appointment with Dr. Abrams had been canceled. She didn’t explain why, and I didn’t ask. I supposed I was in the clear, but I still wasn’t sure. I knew I needed to distract myself, so I buried beneath my covers, legs pulled to my chest, and watched footage of the 9/11 attacks on my phone, falling asleep around the time people started to jump.

I woke up feeling like the bed was going to swallow me. The inescapability of my situation suddenly became real—my adventure in the woods with my brother and Damon, the return of school, the dinners at chain restaurants and nights spent consuming videos after videos of whatever I wished. I was alone and I wanted to cry, but all I could do was breathe heavily even though the air was too flat to provide relief.

Finally I got up and went downstairs. Not a light was on, and the house felt bigger at night. Only the blue glow of the moon came through. Both the living room carpet and the kitchen tile were oddly cold against my feet. I opened the refrigerator and even colder light spilled out. I scanned around and then grabbed a raw steak that had been sitting next to some pimento cheese and wilted celery. I sat on the floor, my bare bottom flattening against it. I tore open the plastic wrap with my fingernails. Then I raised the meat to my lips and took a bite.

It was tough, but I liked the feeling of muscle tearing beneath my teeth, and the pink liquid that dribbled down my chin. It fell all the way to my neck and dried. I kept eating, swallowing chunks that were painful down my throat. I chewed through gristle and strings of fat. I made it about halfway through, and then I gave up. I closed the fridge and threw the steak into the garbage, making sure to bury it deep beneath cereal boxes and unused coupons. Then I went back to bed.

I think I woke up only an hour later. I felt like some kind of animal had made its way into my stomach. For a few seconds, I didn’t know where I was. The dark had rendered everything flat. But the pain was too much, I was on the bathroom floor before I even understood what was happening, staring at a toilet full of vomit.

My mother must have heard me because suddenly she was next to me, rubbing my back and saying soft things I couldn’t understand. She stayed until I had nothing left to throw up. When I collapsed, my knees sore from pressing against the tile for so long, she picked me up by my arms and took me back to my room. She brought me saltines and vitamin water. I didn’t realize how much I was sweating until she pushed my wet hair out of my face.

I stayed home from school that day. I watched TV and fell asleep. My mom came to check on me every once in a while. I had bone broth and butterless toast for lunch. I didn’t throw up again, but I told her I had so she got me more Gatorade.

That night, she sat on my bed and asked what happened with Damon. I didn’t know what she was talking about. In the haze of my sickness, I’d completely forgotten about our game of hide and seek. Then I remembered and felt sick all over again.

My mother, for once, did not seem angry. She had this weird face like she’d stubbed her toe.

“You’re not supposed to go there by yourself,” she said. “Why would you take them?”

I sat with my back hunched, legs hugged to my chest. My chin rested on my knees.

“I was just bored,” I said.

“His parents are really upset,” she said in this strange voice, devoid of anger, almost like she was asking me what she should do, like I was the mother and she was the daughter. “He could’ve gotten hurt.”

“I just wanted to play a game. There was nothing to do.”

She was quiet for a long time. Then she nodded, touched my knee, and left.

Damon never came to our house after that, but my brother still went to his. My mother rescheduled my appointment with Dr. Abrams for the following day. He raised my Strattera from ten milligrams to twenty. It came with bursts of nausea and sleepiness, but I was assured the side effects would wear off in a few weeks.

The heat wave broke again. It rained for the next two weeks, so much that there was a flash flood in the next township over and damaged a few buildings. Our church organized a fish fry to raise money for the repairs. The rain left, but the humidity stayed. I slept above my comforters, naked, and every morning I still found my bed flowery with sweat. Some of the honors students used the flood to organize a walkout to raise awareness about climate change.

One night, towards the end of the semester, when the pavement burned and the air was suffocating, I got invited into the woods by the boys, including James. I had seen him in school, and around the neighborhood, but we never spoke. I always thought back to that girlfriend he mentioned. I wondered what she was like. I wondered if she was prettier than me. I wondered if they’d had sex yet. Sometimes I smiled at him when we came across each other, but he never seemed to notice.

But that night, I saw him, he saw me, and he smiled first. I smiled back.

People brought fireworks and lit them in a clearing. Firecrackers and sparklers mostly, but some were bigger ones too. Somebody made a bonfire, where we threw used condoms and crushed-up beer cans. In hindsight, I don’t know how the cops were never called on us.

Me and the other girls shrieked and ran away from the flames, curling our arms to our bodies and crashing into each other. They were all scared of the fire. I acted like I was too, but I wasn’t. It was almost hypnotic, calling to me, like that story about the burning bush from Bible school, and I wondered what would happen if I stepped on one of the sparks.

As the night wore on, I became dizzy and hung back. My throat burned from Four Loko, which fermented in my gut, and my thoughts kept returning to Damon, to that day in the woods. We couldn’t be too far from where I’d taken him. I sat on a log, brushing dead leaves and twigs off my shorts. I picked at the dirt that collected between my toes and huffed a little.

That was when James approached me. He had a joint between his lips, and he gave me that little nod that boys do, the one more with their chin than their actual head.

“Hey,” he said.

I smiled. “Hey.”

He sat next to me and offered me the joint. I accepted, of course, and impressed him with how I inhaled like I’d been doing it my whole life.

We sat next to each other, our knees bumping, laughing at nothing in particular. I don’t even remember much about what we talked about, I was too busy watching his face in the glow of the joint. It looked different in the dim light. It looked younger, more feminine.

We laughed again. I don’t remember how we got closer, but we did. I saw how long his eyelashes were, I saw how his lips weren’t big but they were full, and I saw the muscles in his neck, which almost looked strained. I thought about touching them, I thought about how they would feel beneath my hands. Would they be firm? Would I feel his breath fluttering beneath my palms? What would happen if I squeezed, just a little?

He kissed me. I almost thought I’d imagined it, but then he kissed me again and asked if it was okay. I didn’t ask about his girlfriend. We kept kissing and went back to his car, and he took off my clothes in the dark and we tried to be quiet. It was nothing but us, the sound of our breathing, heavy and thick, and the squeak of leather against our bodies. Our skin was almost too hot for us to touch each other, but that didn’t stop us. Is this okay? He kept asking. Is this okay? It was sweet.

In the dark of the car, him losing himself above me, I tried to think of the things that excited me. I thought of that video we watched in the basement, I thought of the cats. But none of those things worked anymore, so I returned to that afternoon with Damon, when we were in the woods together, when I was so close to killing him. I remembered it so vividly that the heat of James’ body felt like Damon’s when we were crouching in the clearing. I imagined the sounds he would’ve made with my hands on his, I wondered if they would’ve sounded like James’ now, low, slightly choked. I imagined the his neck giving way to my weight, I imagined his body small and frantic under mine, I imagined his chest crushed beneath my legs, the sweet pressure of it, I imagined spit gathering on his paling lips, I imagined his eyes turning up and then closing, his body going limp, I imagined it again and again and again and then I came.

I still get bored. The restlessness comes and goes, and I don’t know what to do with it. I’ve talked about it so many times, but nobody seems to get it, even though they nod and say that they do. It’s like a splinter. Always there, under my skin, too small to extract. But I don’t feel it as much as I used to. It used to be a roar. Now it’s just a hum, which is almost worse.

Gabriela Gorgas is a writer from Ohio whose work has appeared in The End and Muumuu House. She can also be found on Instagram @gabriela.gorgas and on Substack at gabrielagorgas.substack.com.