By Amber Burke

Casey is confused. She doesn’t remember having met us yesterday.

“These two are going to be living here with us this year,” Glen, the caretaker of this small ranch in Coyote, NM, pop. 71, who has also become his wife’s caretaker, tells her again. “They came all the way from Pennsylvania. They’re going to look after our animals while we’re gone.”

My husband and I are following the white-haired couple down to the horses, accompanied by their dogs, Chaco and Danny. We won’t have to watch the dogs—they’ll be with a neighbor– while Glen and Casey are away visiting relatives for most of May. I’m glad; they discomfit me, these heelers so obese I mistook them, on first sight, for wild boars.

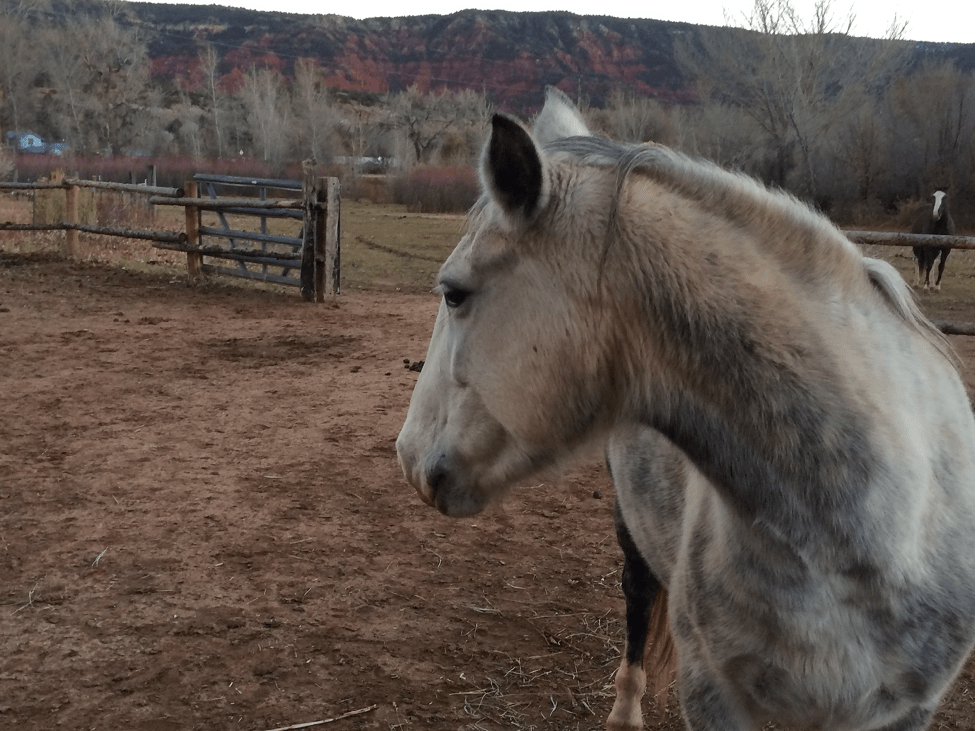

We cross the bridge bestriding the ford where the water is as red as the rocks here, and the horses come to the fence to greet us. Glen tells us their names, and I repeat them aloud: Landy, Sabrina, Cody. Glen wants to take them into another pasture, closer to the barn where he keeps the hay.

We halter the horses, something Mike, who rode when he was younger, remembers how to do and does easily. Glen coaches me: “Get on her left. Loop her neck, then her nose.”

“What kind of horses are they?” I ask as we lead them up the dirt driveway.

“Quarter horses.”

I catch myself repeating “quarter horses” and look at Glen to see if he is irritated by my repetitions, but he doesn’t seem to be. Of course: he lives alone with a wife who has dementia. He would be patient and kind.

“Quarter horses can run fast for a quarter mile,” he says.

“Are they all quarter horses?”

They are, apparently: the red one with the red mane, the red one with the black mane, and the red one that looks to have been snowed-upon. “Sorrel, bay, roan,” Glen tells me, pointing at each in turn. Sorrel, bay, roan.

We bring the horses to a large, fenced-in field. There’s a pony there already; her name is Mamasita, and she doesn’t seem to like the horses much: she keeps to herself. We’ll need to feed them all since there isn’t much for grass yet. “They each get two flakes.”

Flakes?

“Flakes. This much of a bale.”

The horses eat the hay we toss over the fence; I’m surprised by how loudly they chew: the sounds in their skulls must be thunderous.

“Now you know,” Casey says with some impatience, as if she’s trying to get rid of us, even though Glen has just started taking us through our duties.

We go back to their place so Glen can show us the switch in the closet that turns on the water pump.

“Should we be watering the plants?” Mike asks. Bougainvillea clambers up the walls in a windowed hallway where birds are caged.

“Yes. And feed the birds.”

“I love these guys!” Casey says, looking at the green parakeets whose tweeting and stink fill the house. On the wall by their cage, above a couple meditation cushions, is a swath of butcher paper covered with haikus Glen wrote about the moon. If I had worried that Glen–with his askance gaze, his cowboy hat, his silver shield of a belt–would be hard-nosed, his haikus and zafus reassure me.

“Cover them at night with that blanket. Want to show them how, Casey?” Glen says. Casey pushes her glasses higher up her nose and picks up the soft, red throw folded over the back of the rocking chair. “Like this,” she says. We watch her unfold the blanket slowly, expecting her to drape it over the cage; instead, she refolds it and places it back over the chair.

“Now you know,” she says, with finality.

“What were their names?” Mike asks me that night. We’re in bed in our casita, a stone’s throw from Glen and Casey’s adobe house. On these thirty-nine acres, our places huddle strangely close. I think he’s asking about the horses or the dogs, but he’s asking about our new neighbors.

“Are you kidding? Glen and Casey,” I say.

“What do you want me to do with you if you end up like Casey?” He’s teasing me. We’re just young enough that we have a hard time imagining ourselves old.

“Me? You’re the one forgetting the names of the people we spent all day–”

“I’ll roll off a bridge.”

I let him believe he’ll remember how to roll off a bridge. Where the bridge is. The reason he wants to roll. Maybe he will. Democritus, “the laughing philosopher” is rumored to have starved himself to death when his memory began to fade, at the age of 103, apparently remembering he was not supposed to eat and why.

I have not said aloud to my husband, in so many words, that I am worried about losing my memory. I am of the superstitious school that thinks admitting to having so much as a flu might be the tug on the cord that brings the sickness down like a curtain.

My great-uncle on my father’s side had dementia, and my grandfather cackled when he told– and re-told– the story of Uncle Wendell bringing out the snowblower to mow the lawn. And, like too many grandmothers, one of mine had Alzheimer’s. First, her baking suffered; she forgot sugar. Much later, she thought her son was her dead husband. She was not happy to see him.

In 1970, a psychologist named Charles Stromeyer fell in love with a memory.

His project was proving there was such a thing as “eidetic” memory, one capable of calling up a recent image and examining it in all its details, as one would a photograph. He had evidence that such a memory exists, or so he asserted. But there was trouble with his experiment, whose fantastic results rested on the memorious accomplishments of a single subject who happened to be his fiancée. We can imagine Charles, a young Harvard professor, his chin on the plinth of his hand, staring moony-eyed at his Elizabeth, trying to memorize the patterns of freckles on the soft rounds of her face as she looked at ten thousand dots with her right eye, took a pause, then another ten thousand with her left. Would she be able to remember the two precisely enough to combine them in her mind, and see before her a stereoscopic image of a “T”? Yes, it turns out she could, this woman he was going to marry, this woman who could, apparently, remember poems written in a language she did not speak years after reading them.

That Elizabeth refused to redo the experiment is little wonder. Psychologist after psychologist tested subject after subject and failed to find another “eidetiker” like her: even those with the best memories miss things, change things, form imperfect pictures. We can imagine Charles trailing hints, dropping clues, transcribing an equivocal answer as a certainty, giving her hints with his expressions. And out of their combined willing, their conspiracy of longing, was born the child of her memory, which like so many children, was indeed remarkable, yet not as remarkable as its parents supposed.

I don’t think Charles was alone in his desire to have a rememberer for a wife. Isn’t that at least half of why anyone marries? Love me, be my memory, remember for me, remember me.

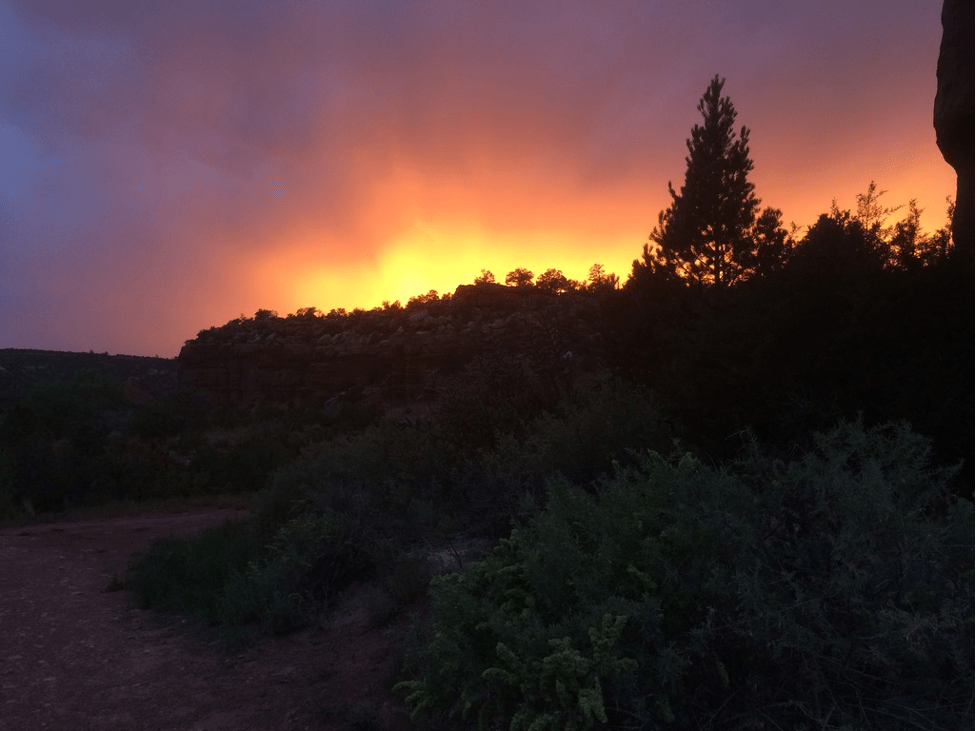

Some days, while Mike is playing his guitar in the casita, I climb up the mesa that borders the property to the north. Up here, the Pueblo people cut arrowheads centuries ago, while waiting for the elk to come drink from the ford. I find piles of chert. Picking up sun-warmed shavings of obsidian, I can almost feel the heat of ancient hands, as if the rocks were dropped just moments ago. And from the mesa, I can see the land.

The topography of New Mexico is the closest I have found to the topography of memory. No gradual slopes here: the ledges of the mesas rise as suddenly as memories rise from the plane of everyday life, disconnected from the time they belonged to; the plateaus are worlds unto themselves, steady underfoot, until their cliffs drop off as suddenly as memories end, what happened next lost over some precipice. Below, the llano is riven by arroyos, as vulnerable to flash floods as the gullies in memory are to the rivers of forgetting. And everything changes with the light.

It is too beautiful here. Sometimes we have coffee outside early, watch the light lift the mist of the mesa and fall over us as it does the trees, and there isn’t a thought in my head. I wonder if the light here is obliterating my memory along with my old worries.

But no one, as far as I know, blames forgetting on beauty.

There used to be various ideas about the causes of forgetfulness. Horace joked that wine was the “true draught” of Lethe. Plato worried that writing would lead to forgetting. Galen, who credited reason, in part, to temperature, thought coldness was the root of dementia. Unlike some of his fellows, Cicero did not think visits to the graveyard were a problem. He wrote in “On Old Age,” “Nor have I any fear of losing my memory by reading tombstones, according to the vulgar superstition. On the contrary, by reading them I renew my memory of those who are dead and gone.” Cicero blamed any loss of memory squarely on its disuse.

I’m making an effort to use my memory. By assiduously learning the names for things—sorrel, bay, roan—I’m supplying my storehouse against an impending winter. Let the mold grow and the rats munch what they will: I’ll still have enough names to get me through till spring.

And by learning new things, obscure things. I read in the cool toolshed, which doubles as a library, housing desiccating books that belonged to the former owner. Some are about psychology, existentialism, Southwest history; most are about the philosophers of Greece and Rome. And sometimes, I can almost see senators in togas walking across the high desert, declaiming to the mesas towering large and grand as acropolises. And sometimes, Athens and Rome turn into deserts where red sand blows, scouring the names and faces from statues.

And because of these books, I’m thinking about the history of memory, when I used to just worry about my own.

“Worse than all bodily ills is the senescent mind,” wrote Juvenal, one of many Romans preoccupied with memory and its feats. Memory and its feasts: In Cicero’s De Oratore, Antonius related the story of how Simonides of Ceos—a Greek commemorative poet, whose job, you could say, was memory—had the good fortune to be called out of a banquet just before the roof collapsed and killed everyone inside. After the disaster, Simonides, using the method of “loci,” or “place,” was able to list the names of all the fallen banqueters by visualizing where they sat. His impressive memory—it was a large banquet—outflanked the collapse of the banquet hall, and Simonides emerged as a kind of hero, as if remembering someone is akin to saving them.

Maybe it is.

The Greeks were nuts for memory. Mnemosyne, Greek deity of memory, was the mother of nine muses: comedy and tragedy, lyric and epic poetry, history and hymns, history and dance, astronomy, which derive from the body of memory, but also show us the past, for, through these forms, we can divine the way the world once was. Lethe, oblivion, was personified, too: she was the daughter of Eris, strife. To name just a few of her siblings, according to Hesiod: Hardship, Starvation, Pains, Battles, Murders, Lies, and Ruin.

The bias is clear.

A sacrifice to Mnemosyne was said to aid one’s memory. No one, as far as I know, made offerings to Lethe. Drinking from the river Mnemosyne, upon arrival in the underworld, was recommended to those wishing for omniscience. I wonder if it was clearly marked, or if anyone confused it with Lethe, the parallel river of forgetfulness.

Perhaps one could tell just by looking at the water: I imagine the water of Lethe is like the red ford here, whose redness, I learn, is from the iron in it. The well water is rust-colored, too.

We drive a half-hour to the nearest gas station to fill our jugs with clear water. The drive is an event, a journey from red rocks to the yellow-striped mesas. Golden light pools in the folds of the painted cliffs, and the ridge of Pedernal, as we pass it, turns like a great, dark ship in a dream.

Certainly, there are things I remember; plunk me down in any city I’ve lived in—Lancaster, Baltimore, Los Angeles, New York, Florence, New Haven, Bismarck–and I will have my bearings; these maps are still inside me, though perhaps stored somewhere sunlit: all street names have faded from them. And if you were to ask me any of my previous addresses in this blur of cities, I couldn’t tell you. Ask me my current zip code, and I’ll tense up. And I’m never sure how a sentence coming out of my mouth will complete itself, if it will complete itself. Sometimes, the horse I’m riding goes right over the edge of the cliff. It is this interior diaphanousness, more than any family history, that makes me think my memory is not long for this world.

It is not new. Before elementary school, I would remind myself of who I was: what I liked and disliked, what I had done, was doing, and wanted to do. Through this conscious act of remembering, I called myself back into existence.

In sixth grade, I saw a photograph in a magazine of a young man’s brain. Not a photograph exactly, some kind of x-ray image. Not a brain exactly. The boy had been having terrible headaches. Upon examination, it turned out he had no brain at all, just a web of tissue, white and vaporous in the dark silhouette of his head, like a bridal veil afloat in a dark pond. The emphasis of the article was on how much he was managing to do with so little. Some sense of recognition, of kinship, shivered down my spine as I read. My recent attempts to verify the story have come to nothing; I don’t remember the boy’s name, or the magazine, or the condition, and sometimes I worry I am remembering something I only imagined.

Casey had terrible headaches, too. By the time a doctor attributed her headaches to fluid building up in her brain and pushing it against the skull–“water on the brain,” adult-onset hydrocephalus– it was too late. Look at a scan of a brain damaged by hydrocephalus: its ventricles become enlarged pools, as if a dam somewhere has burst. What is below the dark water is gone, gone.

Not everyone thinks memory’s where it’s at. Had Nietzsche strolled around antiquity, his philosophy would have seemed as anachronistic as his mustache; it might have been to Lethe he sacrificed his chickens.

According to Nietzsche, all action requires forgetting. Of the person who cannot forget, he writes, “He will, like the true pupil of Heraclitus, finally hardly dare any more to lift his finger.” And happiness, to Nietzsche, depended on forgetting, depended on thinking “ahistorically.” In his Untimely Meditations, he admits a particular jealousy for “ahistorical” beasts: “Observe the herd which is grazing beside you. It does not know what yesterday or today is. It springs around, eats, rests, digests, jumps up again…with its likes and dislikes closely tied to the peg of the moment, and is thus neither melancholy nor weary.” Memory, to Nietzsche, who had a few bad ones, was the source of sadness and exhaustion.

When Nietzsche wrote his paean to forgetting, did he—a man who had long experienced myopia and headaches, who worried the brain ailment that killed his father was hereditary, and who, in 1874, the year of the publication of Untimely Meditations, was having leeches applied to his forehead in the vain hope of relieving his distress—sense the impending loss of his own faculties? I wonder if he already felt fissures in the earth underneath his thoughts and anticipated a near future when he would see a horse being whipped in Turin, fling his arms protectively about her apocryphal neck, then collapse into insanity.

I wonder how much time Nietzsche spent with animals. Did he know how much they do remember?

During our first weeks in Coyote, when Glen and Casey are gone, their dogs wander back from the house of the neighbor tasked with watching them, remembering their house, not understanding why they can’t be in it. Mamasita, the pony, wanders off through a hole in the fence, remembering where she came from: we call another neighbor, Florencio, from whom Glen bought her.

Florencio drives us to the field behind his house, where, he tells us, he used to have a whole herd. There Mamasita is, lifting her head from the sprouting threadgrass.

“She likes it here,” he says. “She likes the grass.”

In the vast field, in front of the gigantic red mesa, she seems lonely and lost. One pony, all those acres, no trace of her herd.

For how long did Nietzsche’s horse remember him, the man with the fine moustache who buried his face in her neck, as if hoping she could save him?

Though horses have excellent memories, they get dementia, too, and become aggressive, forgetting, for example, that they like being ridden. They may feel hungry or thirsty but forget they need to eat and drink. If someone doesn’t take good care of them, they don’t make it long.

Soon after Casey and Glen return, Glen wants to ride the horses “to get the ya-yas out”; horses that haven’t been ridden in months forget what it’s like to have a rider, forget their manners.

It takes a long time to tack them up; Casey, who used to be, according to Glen, an excellent horsewoman, forgets the blanket goes on before the saddle, then throws the saddle on backwards, then tries to put Landy’s bridle on over her halter.

But eventually we’re all in the round pen. Everyone else is on horses; I’m on Mamasita, the pony. Mike tells me I look like a pope. Glen tells me, “You’re moving your hands too much. Keep your left hand still when you’re turning right.” I try to remember to move one hand on the reins without moving the other, but my hands won’t listen: both hands keep moving.

We’re all trotting when Casey stops Landy abruptly. Glen, who was right behind her, pulls up his horse hard.

“You can’t just stop like that. Someone’s gonna get hurt,” Glen says.

“She just stopped,” Casey says, blaming her horse.

“She didn’t. You stopped her. Get her going again.”

“She won’t go.”

“She will. Pop her with the crop,” Glen tells her. “That thing in your hand, pop her with it.”

Casey, who doesn’t like being told what to do, grits her teeth. Glen takes the crop from her, swats Landy’s hindquarters, gets her going. “Let’s try some turns to the inside,” Glen tells Casey. “To the right. No, other way. Right. That’s your left.”

Casey’s hat flies off, and we gasp when she dismounts to grab it without stopping Landy first. She stumbles off the still-walking horse, but doesn’t fall; Glen, horrified, tells her she can’t do that. Casey says he can’t tell her what to do, her jutting jaw leading her homeward. It’s hard to tell if she hurt herself; she always walks with testing steps, as if afraid the earth is about to disappear beneath her feet.

Mike and I dismount at the hitching post, untack and brush our horses. Glen stays to take care of Casey’s horse as well as his own. When Mike and I go back, Casey is standing in the driveway. In her hands, weeds. On her face, abandonment. She looks lonely and lost. One woman, all these acres.

She asks, “Where did that guy go?”

When Glen returns, her face lights up with joy, as if she hasn’t seen him for centuries.

Glen recruits Mike to help him clear the acequias that irrigate the fields by flooding them. Glen asks if I will watch Casey. I say yes, but my heart sinks ignobly. I don’t know how I’ll pass the day with this woman who never remembers who I am, who is looking at me owlishly through askew glasses, white hair unkempt, one jeans-cuff tucked into her boot, the other out.

“She likes walking. She likes rocks,” he tells me before they drive off.

I take Casey for a walk. It is slow going; even so, her fat dogs turn back, giving up. We step over a mattress whose springs squeak underfoot, walk past heaps of rusting cans among the chamisa and the locoweed, spy a single, desiccating high-heeled Mary Jane near a plastic record player, half-eaten by the earth.

I don’t take her north, where the mesa looms; from its high plateau, hoodoos outcrop, their stones perched precariously atop their thin columns like rowboats on chimneys after a flood. The whole mesa is a ship that crashed ashore: deep arroyos stretch outward from it, cleaving the llano like cracks in ice. I steer Casey by the elbow so she doesn’t get too close to one and fall in. I’m leading her south, down to the place where the red ford is banked by an upturned Ford truck turning the same rust-red as the land and shimmering rocks bejewel the sloping earthen walls.

Casey is instantly occupied combing through the rocks. “This is a good one,” she says.

I wonder if some part of her mind is preoccupied by a restless searching which sorting through the stones temporarily allays—if she picks through rocks because she cannot find the memories she is looking for. If the rocks serve as temporary substitutes for all she has lost, all the people and places and names.

Casey tips the choicest rocks into her pockets, like a woman intent on drowning, though her mood is joyful and generous. She proffers some to me, and, if I admire one, says, “You keep it.” I say I will, but when she’s not looking, I drop it for her to find again.

I’m not looking for rocks. I’d like to find a fossil of a snail, clam, or a shark from the time in the Cretaceous period when New Mexico was inundated by a vast, shallow sea.

Or relics from the tribes that used to live here. An arrowhead. A shard of pottery. A fetish: a small stone carved to look like an animal and thought to have a living heart inside. The most valuable of these, Frank Cushing writes in his treatise on fetishes, “are either such as have been found by the Zunis about pueblos formerly inhabited by their ancestors or are tribal possessions which have been handed down…until their makers, and even the fact that they were made by any member of the tribe, have been forgotten.” Forgetting their origins seems to have been necessary to believe in their power.

Casey squats to scoop a handful of cold, red water into her mouth. Looking at her feet, she says, “Bad, bad!” Her boots are coated with red mud; she is close to tears. I don’t like getting mud on my boots either, I tell her. It’s okay: we’ll go back; let’s go back.

There’s an art to it, I suppose. Forget the wrong thing, and you’ll be miserable. Forget the right thing, and you’ll be happy as a beast.

Simonides, the rememberer of names, would have to forget that roofs sometimes fall in order to enjoy the next feast. But he’d also have to remember to eat.

Casey is hungry. We eat the salads I make us on the deck of our casita, the summer sun sending small lizards scampering into the shade.

“Look!” she says, laughing at the purple carrots. “Look,” she says again, turning her attention to the landscape. Never mind that she’s been here for years already, she renews my appreciation for a view I’m already getting used to, the eye-burning red rocks and the locoweed budding yellow under a slab of turquoise sky.

“So good,” she dubs it, like she’s the god who made it.

I ask her if she believes in God. No, she doesn’t. She’s quite firm. I wonder how many of us would believe in God if we could remember who told the first stories about him.

“Look!”

I don’t know what she’s indicating—The cottonwoods? The magpies? The red pond?–but I agree that it is beautiful, and she says, patting my hand, “That’s why we get along.”

My eyes surprise me by stinging, and then she wanders off, back to her house, and when I go to look for her, I find her scraping mud off her boots in her living room. The bathroom faucet is running, running, and she doesn’t remember who I am.

“Where are the guys?” she asks. She could mean Glen, or Mike, or her dogs, or her horses. I tell her where all of them are. I tell her all of them are okay.

Fall sends tarantulas climbing up the outhouse walls like black handprints. There are nights when Casey wanders into our casita, and stands at the foot of our bed, and nights, once we learn to lock our doors, that we see her staring through our window—in her white nightgown, white hair wild– like a worried moon.

“I’ll have fun with you,” Mike tells me. It’s the conversation about my memory again, the one we have each time he finds the knives I threw out in the bushes with the salad scraps, or the groceries I didn’t put in the refrigerator, or the stovetop burner I left on. “I’ll make you all the food I like but you don’t; you won’t remember that you don’t like it. I’ll be able to tell you the same jokes again and again,” he says.

He’s trying to be sweet; he could even mean what he says, that he won’t mind taking care of me. But, sensitive about my forgetfulness, I get mad and go to Abiquiu Lake alone.

This reservoir, which has left no hint of the Tewa hunting ground it overpoured, looks like a mirage, improbable and beautiful here in the high desert. I spread a sheet out over the rocks in an ear-shaped inlet. There are bone-like white boughs protruding from the water, their reflections grabbably precise, and bleached branches litter the beach like fallen antlers. The sun is directly overhead, and I think myself clever for taking a sheet out of my basket and draping it over the branches to create a shelter. From under it, I look at the blue water reflecting Pedernal, the jaw-like mountain where Changing Woman, who made the Navajo world, is said to still live, changing with the seasons from a baby to an old woman every year.

After a while, I leave my shade and go into the water slowly. I’m walking, feeling stone then silt under my feet, then I’m floating, then I’m swimming, and I’m glad I am, and this is it: this is the place to be in all the world, and I have it to myself.

But even as I’m here, I’m not; days I spend alone are days that vanish. The day goes right through me, like it’s not there at all. That sky, my husband said in Paris, and for the first time, I looked up, and the sky was there: gray, with fast-blowing clouds. Later, he’ll recall this church, that train, the town with the stone hut where the solstice sunlight treacled in, and these memories will come back to me. He is the memory that walks beside me.

I’m his memory, too. We ask each other the questions millions have asked their beloveds since time immemorial: Have you seen my keys? Where were we when? Who was that? What were their names? And in this way, in the cradle of our minds, we protect each other against the wastage of time. Without him, it would be as if I weren’t here at all.

My arms and legs and anger disappear into the water.

Imagine: you’re on a trip to the underworld with your beloved, the two of you heading for the Elysian Fields. You put your binoculars to your eyes to get your bearings. When you lower them, you see your beloved bowing to drink from Lethe. You’re sure it’s Lethe. You yell, “Stop!” but it’s too late. You look into the eyes of your beloved, waiting to see if they will recognize you. Because if they don’t, you’ll disappear.

Winter is quiet. Smoke rises from Glen and Casey’s chimney as it rises from ours. It’s not the snow that keeps us indoors as much as the knee-high red mud the snow melts into every afternoon when the sun comes out. Still, I get restless, and I squish my way down to the horses. They huddle together by the trees, coats grown shaggy, flecked with mud and burrs. I offer them carrots, and they walk to the fence reluctantly, breath coming from their nostrils like smoke. They seem to have withdrawn somewhere inside themselves, waiting for winter to pass: their eyes seem distant, like Glen’s have been when we’ve knocked.

We get a dog, a puppy from a neighbor, and name him Shep. One day when Glen and Mike are mending the fence through which Mamasita has again escaped, the puppy disappears when I’m getting wood from the pile.

I look all over. I call for him. Spring almost came, but now it feels like winter again: too cold for a puppy on his own. I hope that Casey took him into her house, but the door is closed, and she isn’t answering my knocks. I finally let myself in and discover her kneeling by a plastic bin of dogfood, feeding her dogs, feeding my puppy, handful after handful from a plastic bin, as if in a trance.

Shep runs toward Glen and Casey’s house again and again after that, remembering full well the place where he was allowed to eat and eat.

It could have been worse. The propane truck that broke the narrow bridge, snapping it in two, and fell into it nose-first, did not leak; it did not explode; the ford did not erupt into flames; no one was hurt.

But Casey can’t sleep the night after the bridge breaks. She knocks on our door upset. “He’s gone! He’s in the ford!” It’s spring, and the ford is rushing with snowmelt. We can hear it from our casita.

“Who?” I’m worried that she is talking about Glen.

“That guy!” She’s almost crying.

Glen comes out looking for her, and Mike joins me at the door; no, she wasn’t worried about either of them. The puppy? I show her our puppy, sleeping in his crate. “He’s right here.”

She looks at me like she suspects me of some trickery.

“Time to go, Casey,” Glen says.

“I hate you,” Casey says.

Glen looks tired when he guides her back home.

It’s late spring; the ford is flowing hard and as fast as the year has gone, red water rushing. I hug the horses goodbye, grabbing hold of their strong necks, breathing in their good horse-smell.

“We’ll miss you,” Glen says, and we say the same, our words lifting and stretching in the wind. But it’s not goodbye yet: the bridge is still a ruin. Glen tries to smooth the route through the ford with his green John Deere tractor so we can get out in our van.

“Goddammit!” The tractor keels over, and Glen curses, tells us to wait: he and Casey will go get a neighbor’s bulldozer to heave the tractor out.

We don’t wait; there something desperate in our departure from this place we have loved. Our van rides low and gets stuck in the mud mid-ford, next to the felled tractor. Mike sloshes in and pushes it from behind, feet sinking into the red clay, while the wet puppy and I stand on the far shore.

“Don’t let him drink,” Mike says. It’s too late; the puppy is already drinking.

We do see them again, Glen and Casey, before she forgets how to swallow.

They come to one of my husband’s shows in Taos, where we just moved; Mike is playing folk songs on stage at a bustling inn downtown. I almost don’t recognize them, the white-haired pair walking, slow and tentative, into the hubbub; they seem strangely denuded and fragile without the field and red rocks behind them, without the horses and dogs. I don’t know the name for my feeling for them, which is tender and heavy. I don’t know if I can change pace, if, right now, I can sink in, sink down into their heavier gravity.

I hug them, and it’s so easy I can’t believe I thought it would be hard; we sit together. Casey loves Simon and Garfunkel, knows, somehow, still, all the words to “Bridge over Troubled Water,” which Mike is singing, to which she sings along, bobbing her knee. In this town among tourists with their new, bright clothes and their definite plans, these two, in their faded, course denim, mud on their boots, are figures from another world, transported through the sludge of space and time, into this world that we’re clinging to as if it will last, as if its ceilings won’t fall, or, as if, should they fall, there will be someone left to stand on top of the rubble, on top of all the rubble, pointing to each of us and calling us by name.

Sometimes the moon presses its face to the window like it’s trying to come in, or something else reminds us of them, and Mike asks, “What were their names again?”

“Glen and Casey,” I say. Their names are sealed to a landscape that has settled into me; I can’t imagine forgetting them. But sometimes I think there could be something wise in the forgetting of names. When names seem to unhinge from their bearers, to belong to them less inextricably, perhaps we are glimpsing that we’re all made of the same stuff, that nothing belongs to any of us forever, not even our names.

We left Coyote because if we didn’t go, we’d surely have forgotten we wanted to go; we would have been lost, the van would have sunk like the tractor was already sinking; it would have become part of the bank like the old ford, part of the land like the half-buried mattress, the curling high heel, the record player that belongs to no one anyone knows, that might as well have belonged to the gods.

I did find an arrowhead, on top of the mesa, before we left: right there, on a patch of red dirt open as a palm, an obsidian birdpoint so clean that it looked newly made. The earth held it up, right where I was about to step, the way memory holds up things from years ago as if they just happened yesterday, the way it still holds up Glen and Casey, even though she has passed away and he has moved on with his horses.

Amber Burke graduated from Yale and the Writing Seminars MFA Program at Johns Hopkins University, and she teaches writing and yoga at UNM-Taos. Some of her work has been published in The Sun, Michigan Quarterly Review, X-R-A-Y, The Gravity of the Thing, and Superstition Review, Barren, Flyway, and Quarterly West. She’s also been a regular contributor to Yoga International, which has published over 100 of her articles and the yoga ebook she co-authored, Yoga for Common Conditions. Her work can be found at https://amberburke3.wixsite.com/amberburkewriting.

Leave a reply to 3rd Annual T Paulo Urcanse Prize For Literary Excellence – High Horse Cancel reply